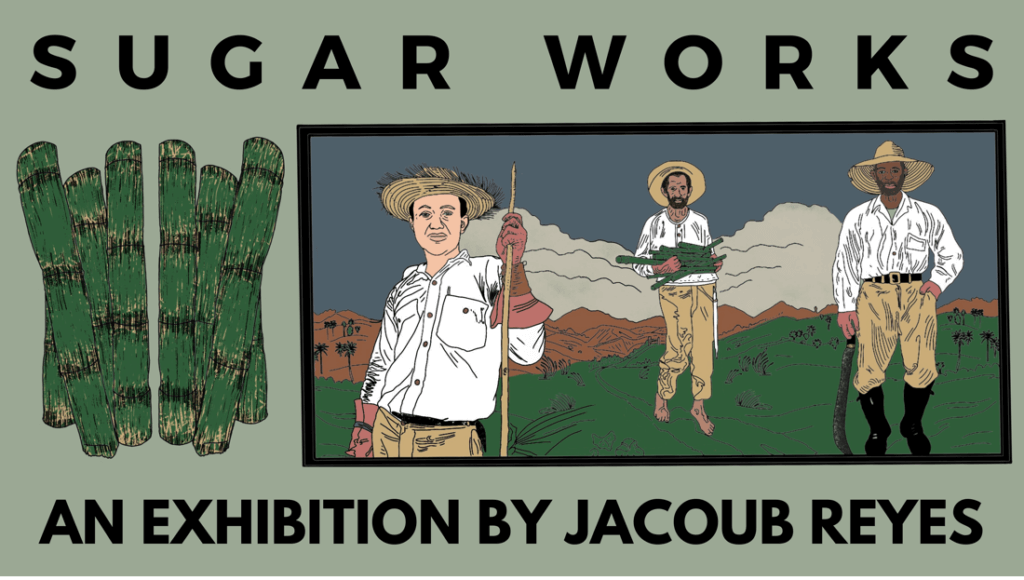

Sugar Works is the culmination of my year-long residency with the UCSF Library and is comprised of woodcuts and accompanying woodblock prints. It explores the sugar and tobacco industries and their influence on the Puerto Rican people, the land, local and global economies through colonialism. My research revealed a complex timeline of events that continues to shape Puerto Rico, its laws, and its livability for the native population. Sugar Works is now on display on the main floor of the Kalmanovitz Library at Parnassus Heights.

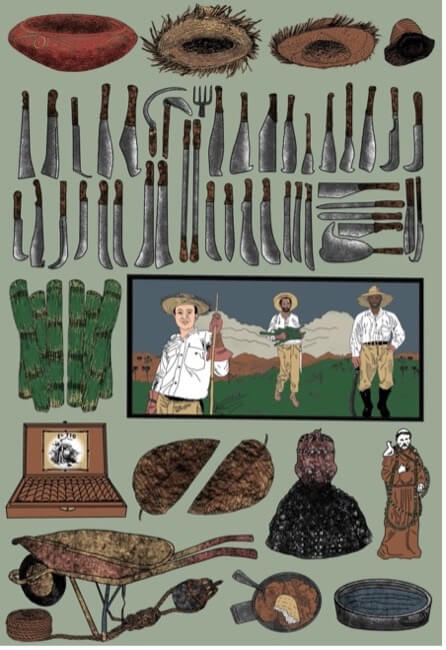

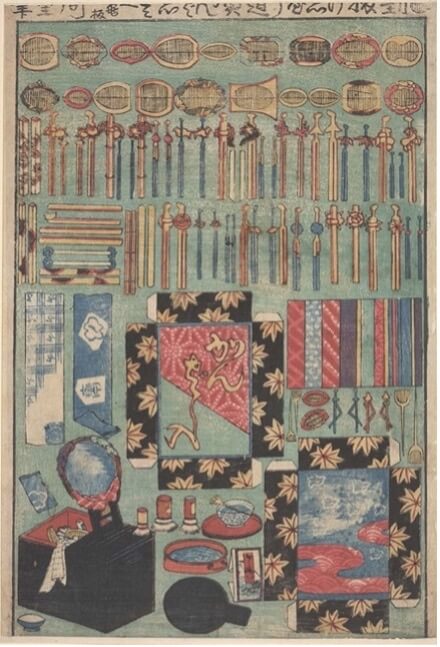

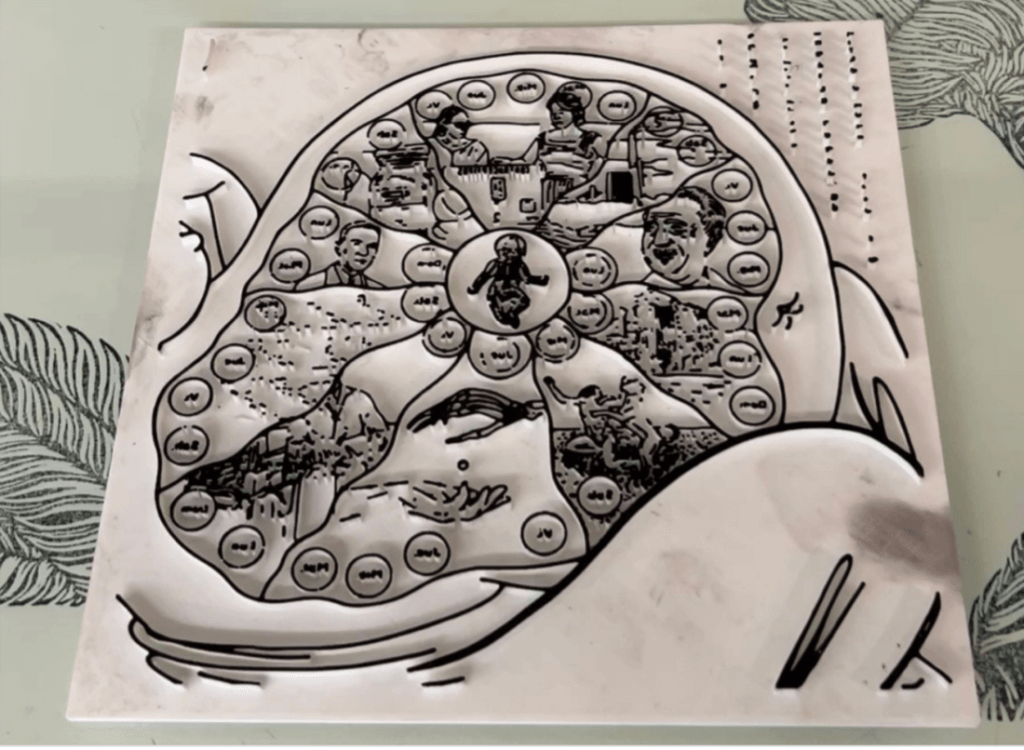

My final workshop and artist talk titled “Tradition, Craft, and Technology: Making Woodblock Prints with New Media” built off my research within the UCSF Archives and Special Collections and showcased the process and materials I used to create woodblock prints in traditional and non-traditional ways. I utilized various technologies to create my images and woodcuts while collaborating with the UCSF Makers Lab. I presented my trials, errors, and findings that ultimately led to successful final product. During this presentation, I also revealed the final woodblock design in my series, “Herramientas del oficio,” an image that included Taino artifacts, Santeria alters, saints,famous Puerto Rican paintings of Jibaros, various sugar cane machetes, straw hats, foodstuffs, packaged cigars, and other items.assortment of hair accoutrements and ornaments), from the UCSF Japanese Woodblock Collection, inspired this image. I selected this image to connect traditional Japanese advertisement images and rural Puerto Rican daily life and work, and a representation commonly erased from American history book pages.

Exploited (Puerto Rican) farmers, also known as “colonos” and “campesinos,” were rural workers tied to the land, often with a status similar to that of sharecroppers in United States history. The landowners established a system where farmers provided their labor in exchange for either access to land or room and board. Colonos’ social identities were constructed at the turn of the twentieth century. Scholars argue that these identities were based off an emerging concept of eugenics, which both American and Puerto Rican educators believed would improve Puerto Rican education. Through this, knowledge about the self and the “Other” was socially and biologically constructed (Nieves, 2014).

Education from a colonial lens

Education was crucial in the Americanization of Puerto Ricans under United States colonial rule. Immediately after wresting Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, the United States began opening schools nationwide and importing teachers from different states. Puerto Rican teachers were also trained in the educational ways of the conquering nation (Navarro-Rivera, 2009). The history of assimilation in the United States is widely seen as an outcome of immigration and the price of achieving the American dream. Assimilation is defined against racialization, but during times of conflict like the Spanish American War, people were challenged and consolidated in the United States. Students were incorporated into stratified society as racialized and colonized subjects and were viewed on how they resisted that incorporation (Ramirez, 2019).

Information as resistance

As technology continues to push onto the fringes of society, tradition begins to change and take new forms. New ways of disseminating information and educating the public through memes, social media, and other avenues often produce viral bits of false information which are detrimental to society in the short and long run. Properly conducted research is vital for adequately dispersing reliable information to communities of various ages and abilities. Research that examines historical trends, narratives, special collections, and archives, much like this project, can unveil harsh realities that must be addressed. It is also important to consider practical approaches that directly affect communities of color.

The intersection of technology, medicine, and humanities can help establish new modes of thinking and perceiving areas and people that are often overlooked. Researchers, physicians, and community leaders can find ways to integrate and implement ethical programming and data collection methods by finding overlapping research initiatives that aim to understand similar issues impacting BIPOC communities. Historical mistreatment of black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in healthcare and research has fueled mistrust and a reluctance to participate in the healthcare system as a whole. In community-engaged research (CEnR) and patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) studies, patients are valued more than research subjects. Instead of a standard research process, these processes integrate lived experiences in questions and data sets, design research for relatable content and language, and build trust through community partners and collaboration. Participants can feel that they have a stake in the process rather than an experiment subject. There are many benefits to BIPOC people participating in health research. Research findings that include subgroup analyses can help tailor results and recommendations to improve health equity and heal health disparities in BIPOC populations in the United States. The historical mistrust of medical research in BIPOC communities stems from abuses that took place via studies designed and led by white male doctors (Edwards et al., 2020).

Decolonizing education

Education is dependent on the governing people and powers that disperse information. In recent years, the conversation over grade-school history books and making certain historical information accessible has been up for debate (Schulten). “Decolonizing culture requires actively deconstructing notions of the other based on the enduring legacy of colonial relations, beginning to understand the meaning of difference, its micro-politics as well as its sociological/historical/ economic/political context…” (Cruz & Sonn, 2011). By raising awareness of socio-historical contexts, reclaiming culture through self-representation, understanding identities, and confronting power structures, people of color can work toward centering themselves in their histories. Scrutinizing information and holding institutions accountable will benefit future generations and encourage independence and autonomy. We must collectively vouch for equal, unbiased access and opportunities for marginalized communities.

The fusion of art and technology

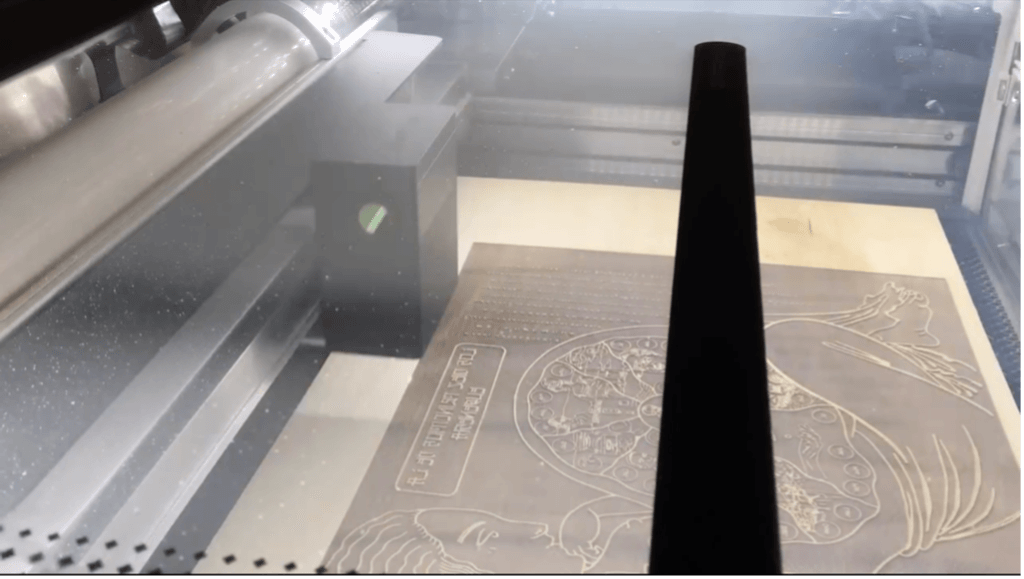

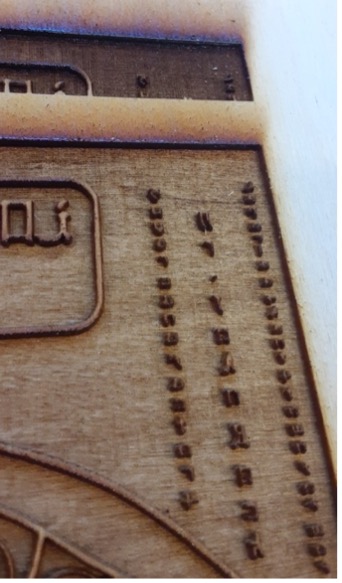

This project combined my archival research with artistic scholarship through experimentation. I pushed my traditional printmaking methodologies by collaborating with the Makers Lab to integrate new technologies into my printmaking practice. Historically, wood carving is a hand-powered craft with a rich history that spans cultures worldwide. The original method relies on chisels and gouges to carve out areas of the material so not to transmit ink. The untouched surface is then inked and transferred to paper or any substrate, like a stamp. By utilizing the Glowforge laser cutting machine, I “carved” away parts around intricate lines and words. This process allowed me to get significant detail in a small area, something I could not achieve by hand.

Utilizing technology has benefits, but it also comes with many challenges. To get the desired depth and clarity, the woodblock had to be lasered at least four times, which caused great stress on the machine and led to motor malfunction. The project required pivoting several times. I attempted to create relief prints from 3D printed matrices, inverted images, and shallower cut pieces. The 3D printed results were varied and did not produce a desirable outcome. Understanding the benefits and limitations of these technologies allowed me to embrace them as another tool in my toolbox. The final boards used in the exhibition have all been etched using the Glowforge, with a variation of the original design plan. Traditional woodcarving allows the artist to interpret and “respond” to lines within their designs. It has little to no dust and provides a unique look that computers and lasers can rarely replicate. For me, this was an affirmation that artists (and humans) will still be necessary even with technology.

Final thoughts

Allyship is essential for creating an inclusive future. Building an environment of trust and accountability will benefit everyone in and outside of academic spaces. In my practice, I aim to analyze information, hold institutions accountable, and work directly with marginalized communities to amplify stories and voices that add to our growing narratives. I look forward to examining the loopholes, gray areas, and in-between spaces to lead to meaningful connections. Through this, I created a framework to uphold tradition, upend racism, and uplift communities of color.

Works cited

Nieves, B. (2014). Imagined Geographies and the Construction of the Campesino and Jíbaro Identities. In: van Wyk, B., Adeniji-Neill, D. (eds) Indigenous Concepts of Education. Palgrave Macmillan’s Postcolonial Studies in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137382184_3

Navarro-Rivera, P. (2009). The Imperial Enterprise and Educational Policies in Colonial Puerto Rico. In: Young, M. (2010). [Review of Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State, by A. W. McCoy & F. A. Scarano]. Pacific Historical Review, 79(3), 491–493. https://doi.org/10.1525/phr.2010.79.3.491

Ramirez, C. (2019). Indians and Negroes in Spite of Themselves: Puerto Rican Students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. In: Molina, N. (2019). Relational Formations of Race: Theory, Method, and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520971301

Edwards, H. et al. (2020). Six ways to foster community-engaged research during times of societal crises. In: Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Volume 9, Number 16. Becaris Publishing. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2020-0206

Schulten, Katherine. “Banned Books, Censored Topics: Teaching about the Battle over What Students Should Learn.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Sept. 2022. www.nytimes.com/2022/09/22/learning/lesson-plans/banned-books-censored-topics-teaching-about-the-battle-over-what-students-should-learn.html

Reyes Cruz M, Sonn CC. (De)colonizing culture in community psychology: reflections from critical social science. Am J Community Psychol. 2011 Mar;47(1-2):203-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9378-x