This past fall, I had the opportunity to host my first virtual workshop as the “UCSF Library Artist in Residence: Storytelling During a Pandemic” (slides). The workshop explored how different storytelling mediums have been used to tell the narrative of the COVID-19 pandemic, through still images, comics, podcasts, animation and social media. These methods of storytelling have served to educate on the science of COVID-19, encourage preventative practices (such as mask-wearing), and give us a snapshot of the daily lives of individuals at this unprecedented moment in history.

Although it would have been wonderful to host the workshop in person, four different sessions were conducted virtually for the UCSF Makers Lab, the UCSF ARCH wellness week, the UCSF Healing and Activism Conference, and the Bay Area Science Festival. During the last portion of the workshop, I led a fifteen minute comic creation exercise as an example of how we can utilize storytelling to reflect on our thoughts, as we experience living through this pandemic. Each workshop followed the same pattern as explained below.

Agenda

- Introduction (5 min)

- Storytelling (30 min)

- Comic Exercise (15 min)

- Q&A (10 min)

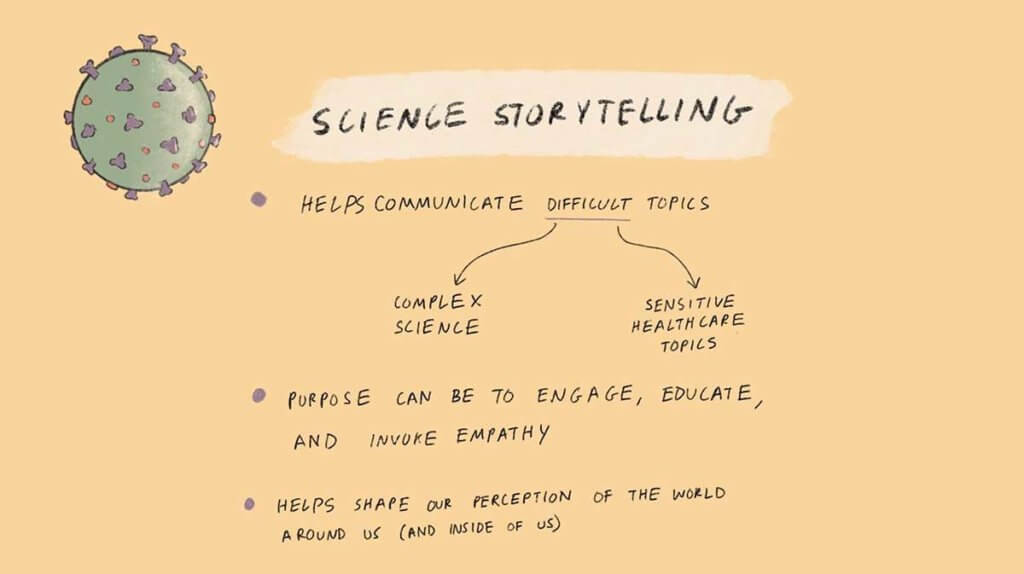

What is science storytelling?

The craft of visualizing the sciences falls under many labels: medical illustration, biomedical communications, art in medicine, etc., and the methods used extend far beyond what was possible during Frank Netter’s popular works of hand illustrated anatomy. Today we utilize AR and VR (augmented and virtual reality), 2D and 3D animation, graphic medicine (comics in medicine), UI/UX (user interface/experience) design, data visualization, digital/traditional illustration, and interactive media, which all incorporate an element of scientific storytelling.

Science storytelling helps communicate difficult topics in science and medicine. Difficult could mean that the science is complex and needs to be simplified for a lay audience, or it could be that the topic is emotionally difficult to process and requires an element of care in how it is delivered. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, new research continues to be conducted in labs around the world to help us make sense of the virus. Science communication and visualization have played a crucial role in distilling this information to the general public in a way that is engaging and approachable. Outside of the lab, people from all walks of life have been affected: from getting sick, being a front line worker, losing a loved one, having to stay home. Communicating these personal stories has been equally important in providing context to the statistics and data, and have helped invoke empathy in order to encourage preventative practices.

Storytelling during the COVID-19 pandemic

Over the course of the pandemic, I’ve been collecting examples of COVID-19 storytelling. During the workshop, I discussed a few examples that cover different forms of media. No form of media is confined to a specific age group or purpose — even comics have wide reach in older audiences.

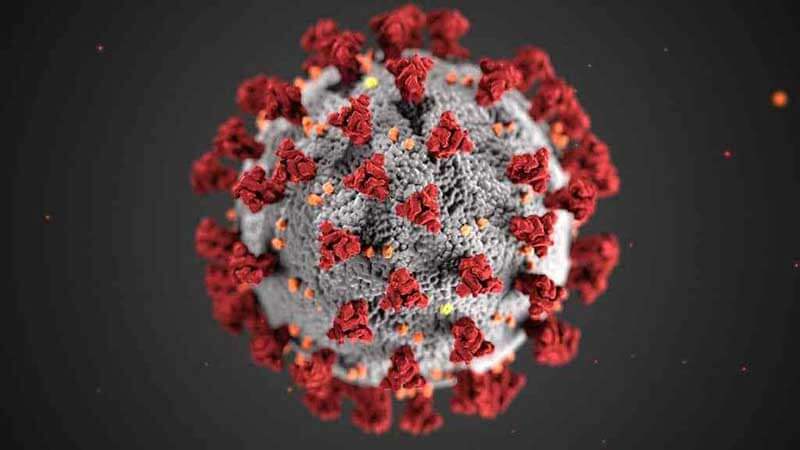

Still media

I had to start off with the now infamous COVID-19 3D render created by CDC medical illustrators Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins. The stony grey sphere with red spikes has been seen in every corner of news media as the world has covered the rise in infections and deaths. In terms of storytelling, this single still image has given a face to the cause of the pandemic, and helped bring to life (so to speak) a main character to the COVID-19 story. The design decisions, from lighting to color palette, are to serve specific functions. From an interview with the NYT, Eckert says the decision to use realistic lighting and textures was to “help display the gravity of the situation.”

Still media can also be used to deliver large volumes of information in one image, as seen in scientific visualization specialist Avesta Rastan’s infographic “The Science Behind Covid-19.” In an online workshop, Rastan explains that the layout of the infographic guides the viewer through a natural reading order, delivering the information in a narrative arc similar to many stories: an introduction, a progression, an impact (climax), and a resolution. Such infographics are effective in that they can easily be shared across social media and disseminate important information.

Comics

Comics are commonly thought to be geared towards a younger audience, however, they are compelling storytelling mediums for heavier topics. In a two-part comic “Fruitilla (part 1, part 2),” illustrator Fran Meneses (Frannerd) shares her story experiencing a miscarriage during the pandemic. Although the comic does not explicitly discuss COVID-19, it is the subtle details that signal this occurred in 2020: wearing masks while walking outside, entering the hospital without her partner, the medical staff wearing masks during the appointment. Illustrating such stories helps us understand how the pandemic has compounded already difficult situations.

Comics can also be approachable educational tools for all ages. Medical illustrator Christine Shan’s comic “How does the COVID-19 Virus Infect Humans?” playfully weaves a narrative with contextual information, introducing COVID-19 and furin enzyme as characters that interact. The goal here is to inform younger readers about COVID-19, without the pressure of it being scary or overwhelming.

Such examples fall under the umbrella of Graphic Medicine, which explores how comics and graphic novels can be used in patient education and telling healthcare stories.

Audio

On the other end of the storytelling spectrum, audio stories such as podcasts, allow the listener to engage with a story on an intimate level. In response to both the pandemic and the police killing of George Floyd, healthcare podcast The Nocturnists, created by Emily Silverman, MD, launched a series called “Black Voices in Healthcare” in collaboration with Ashley McMullen, MD and Kimberly Manning, MD. In a clip from the “Pandemic” episode, a 3rd year medical student describes her internal dilemma with studying for the USMLE Step 1 in the context of a global pandemic: “what’s an eight hour test compared to a pandemic that doesn’t seem to be ending anytime soon and over 130,000 lives lost.” Through voice and imagination, you can close your eyes and place yourself at the scene, and feel the weight of the narrator’s emotions through inflection and tone.

Animation

A combination of both visuals and audio, animation offers a dynamic and immersive way to tell a story set at a certain pace. At the start of 2020, concerning stories from Wuhan, China were making their way into global media. The images, statistics and early data surrounding COVID-19 soon led to increased xenophobia in the West, and a disregard for the wellbeing of others as fear and denial overwhelmed many.

2D animations such as “My Boyfriend Died of COVID-19,” produced by the Atlantic, helped shed light on stories coming from Wuhan and serve as a reminder that behind each COVID-19 statistic is an individual who had their own story to tell. The 2D animation style emphasizes certain words and symbolic imagery. For example, we can see the face and eyes of the narrator (who lost her fiancée to COVID-19), but not the features of her fiancée, who quickly becomes part of the faceless statistics of those who have died during the pandemic. Stories like this help to reshape the narrative surrounding Wuhan, and the misconception that this virus does not affect young people.

Alternatively, 3D animation allows for more flexibility in visualizing complex spatial and temporal relationships. A 3D animation, “COVID-19 Animation: What Happens If You Get Coronavirus?” produced by Nucleus Medical Media, visualizes how the COVID-19 virus functions, and how it affects the human body. The viewer is able to deep dive through the lungs down to cellular and microscopic levels to better understand the science behind the pandemic, and in turn better understand their own bodies and the urgency of preventative practices. The need for compelling, informative media is clear: over 20 million people have viewed the animation since it was published in March, 2020.

Social media

Social media is interesting in that it both produces its own unique type of media based on the platform (Twitter threads, insta-stories, etc), but is also a method for easily sharing all the forms of media mentioned above (infographics, animations, etc). From bite-sized comedic commentary, such as comic artist Alex Krokus’s take on “self-reflecting” during quarantine, to text heavy “instagram powerpoints” such as Carter Wright’s account on his experience testing positive for COVID-19 twice, social media has been a mirror (at times distorted), to life during the pandemic.

Telling your own story

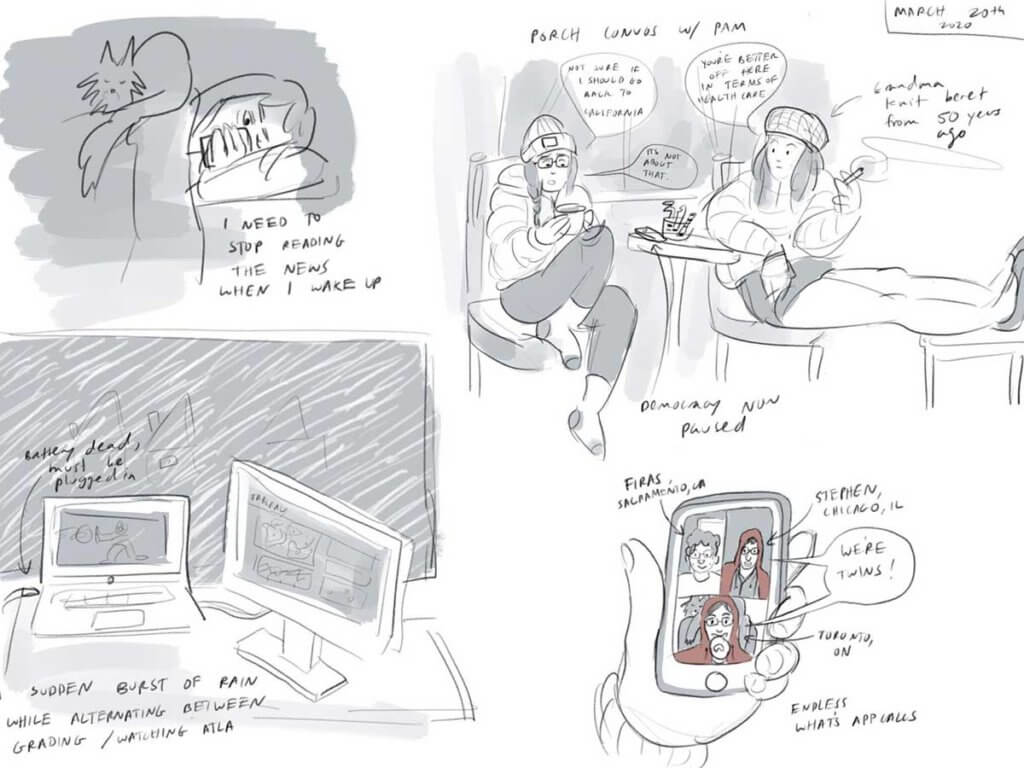

During a year where time feels warped, and everyone is experiencing challenging circumstances, having a way to reflect can be healing. As a visual artist, I find drawing (doodling) out my day and feelings helps me process my thoughts, and document my experiences. For others this could be writing, moving your body, singing.

Doodles from during the first stay at home order in Canada (March 20, 2020), which included obsessively checking the news, adjusting to working from home, and video chats checking in on family and friends.

Comic exercise

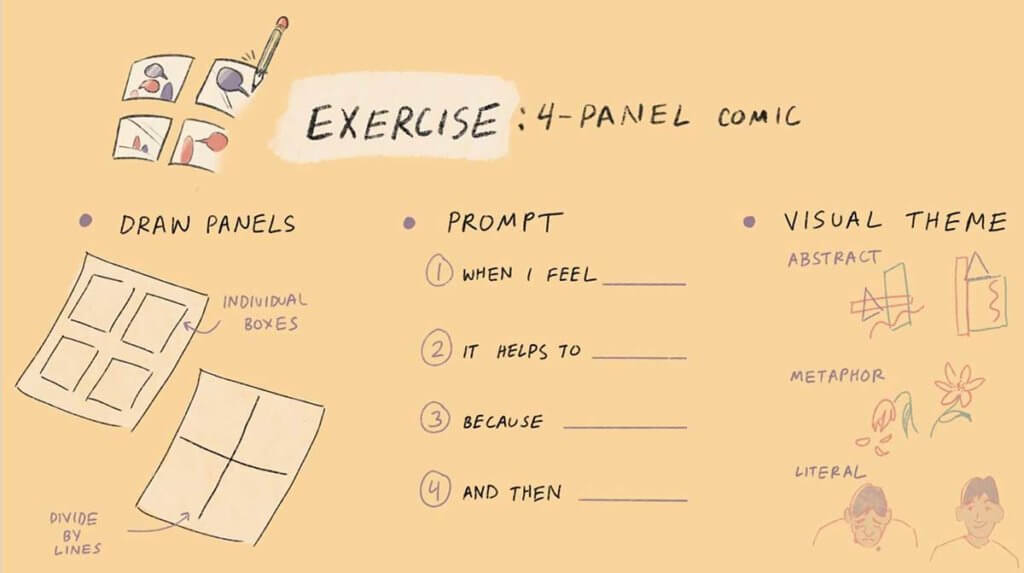

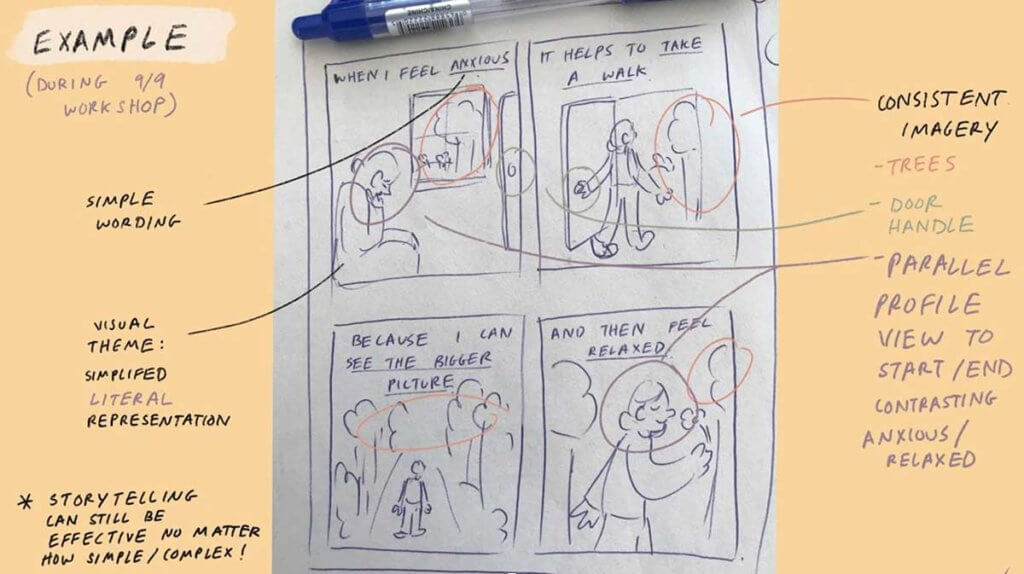

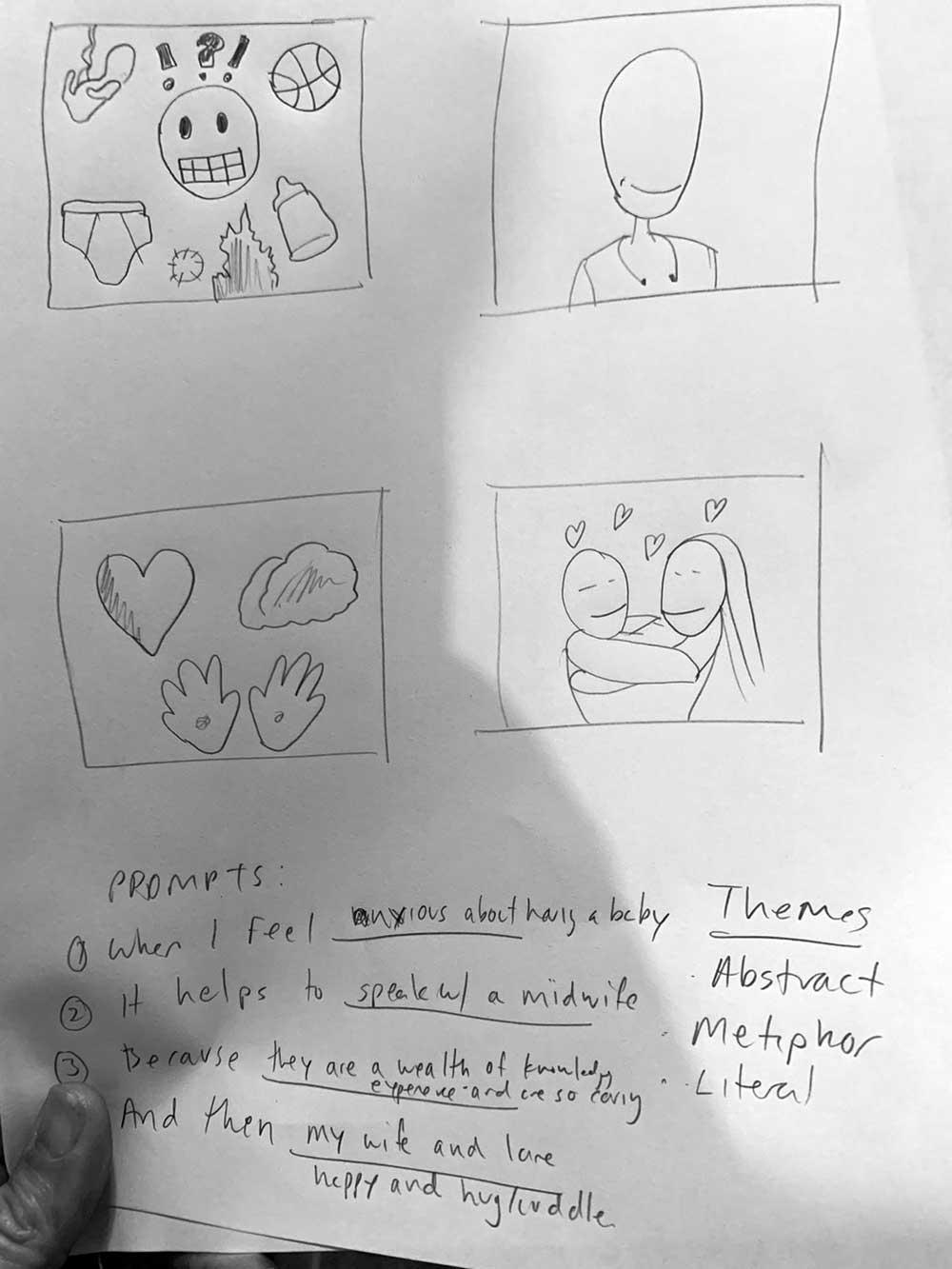

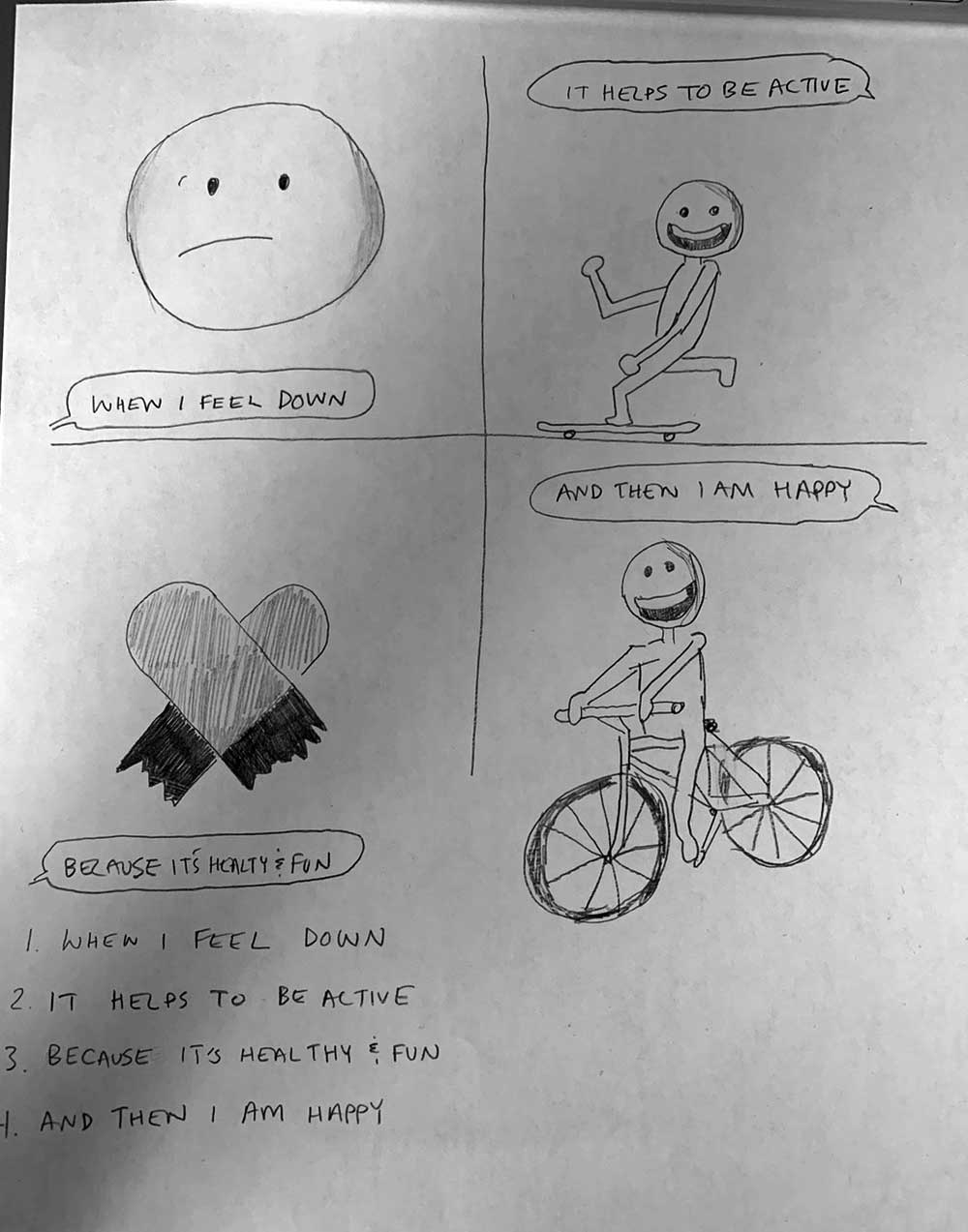

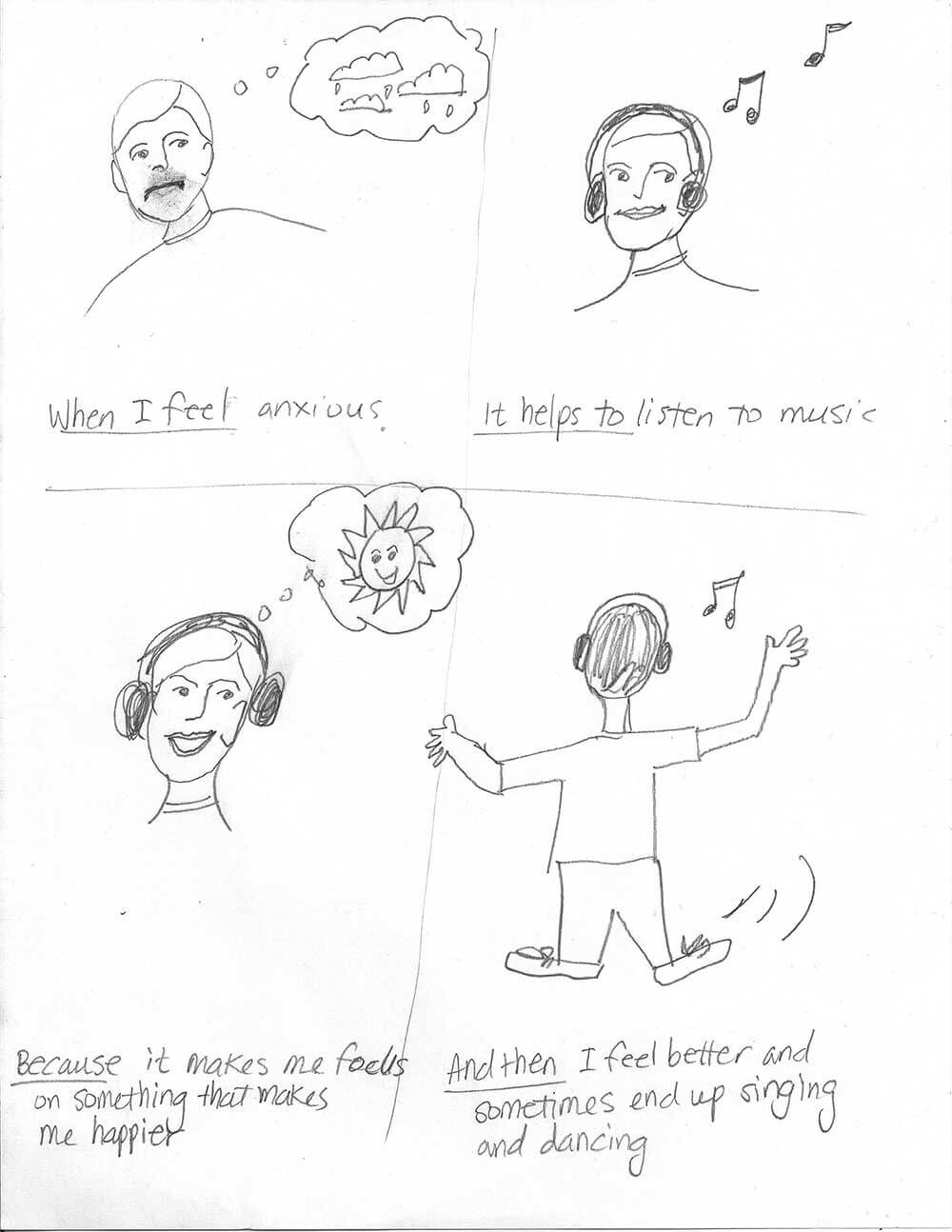

At the end of the talk, we went through a short 4-panel comic creation exercise as an example of a simple method to tell your own story. The exercise was created by Marek Bennett as a visual diary, and starts off by creating 4 panels on a paper. Next, you fill in the prompt for each panel: When I feel _____, it helps to _____, because ____, and then ____. You can then pair each phrase with a simple visual, which can be as abstract or literal as you’d like.

Sharing these comics together at the end of the exercise was extremely rewarding. I appreciate being able to share a moment of reflection with everyone who attended. Although the exercise may be simple, I found that common themes revolved around feelings of anxiety and depression and shed some light on what many of us have been feeling throughout this pandemic. It’s important to remember this one tool of many that can be used for self-reflection, and that every story is worth telling.