This week’s maker is Brandon Cowan, MD, resident research fellow in the East Bay Surgery Program. Let’s take a look at what they made.

Q: What did you make?

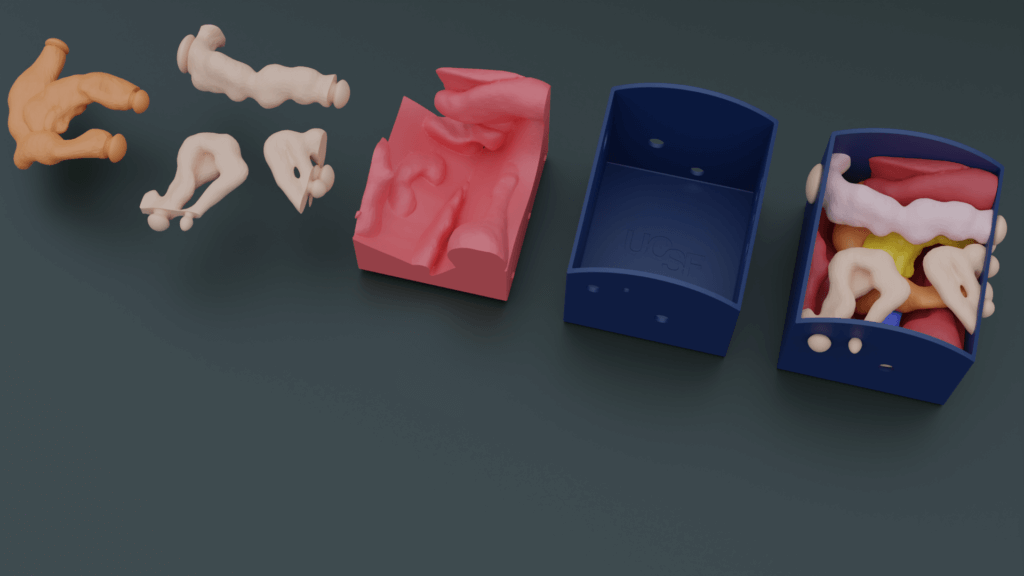

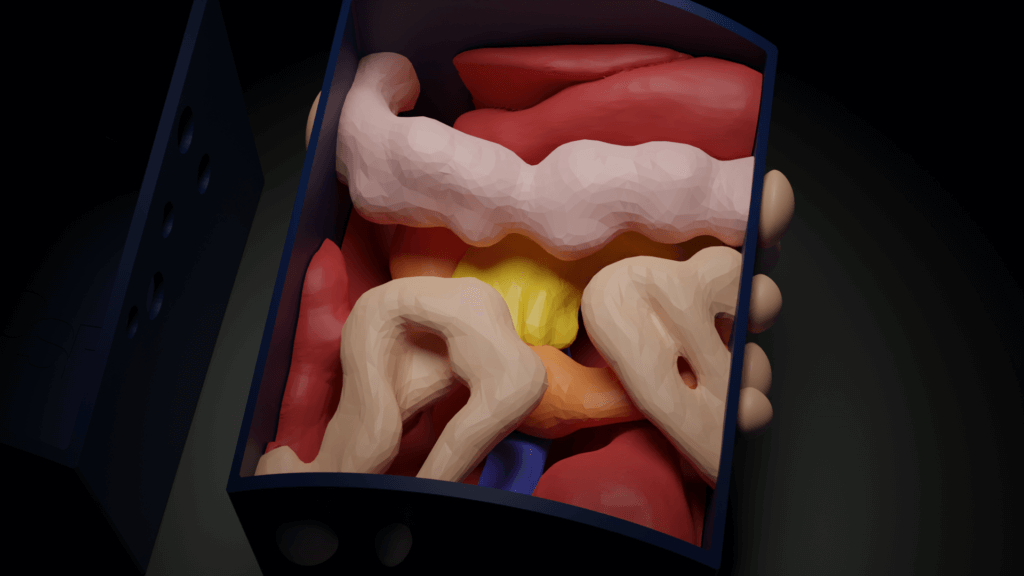

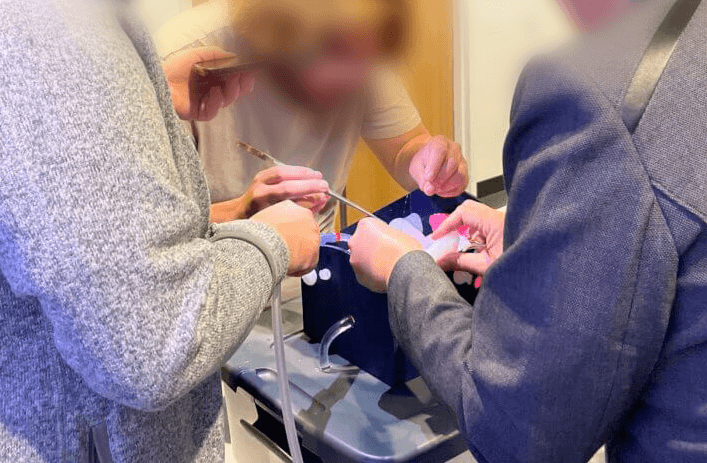

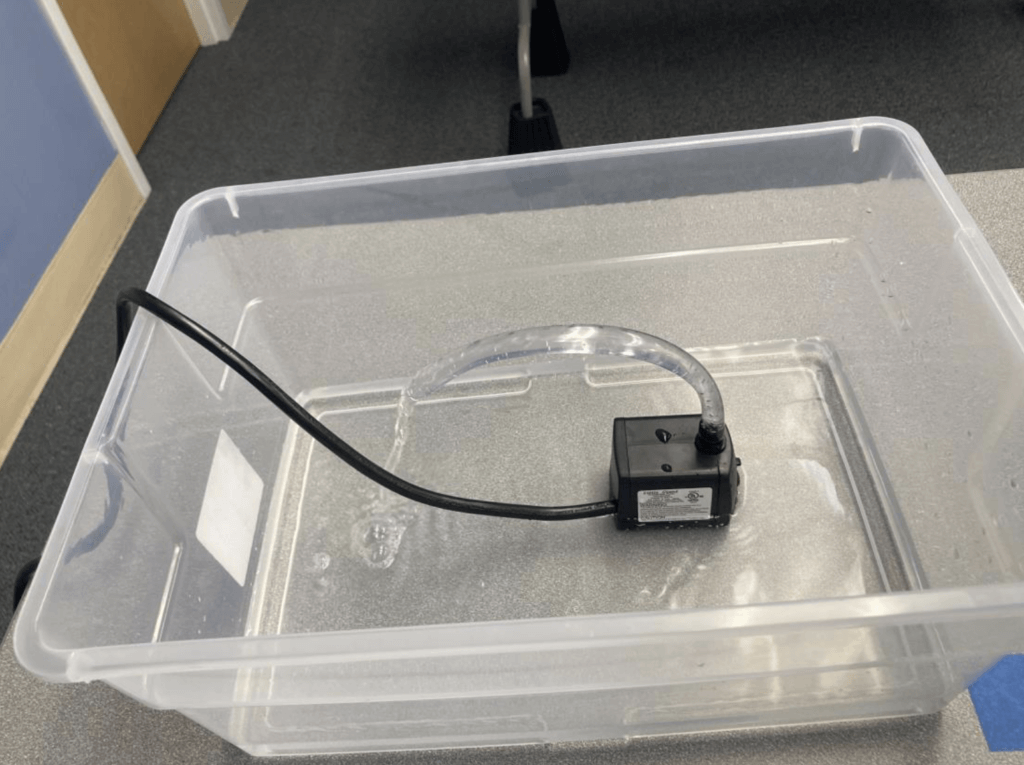

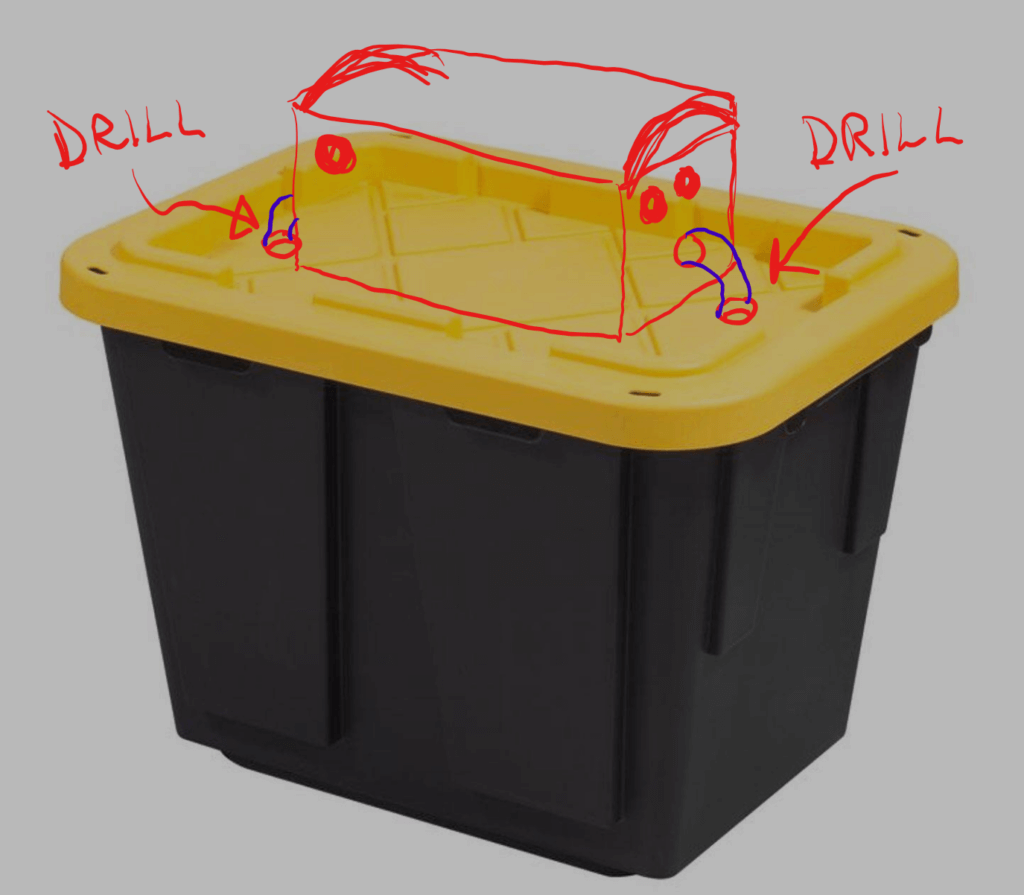

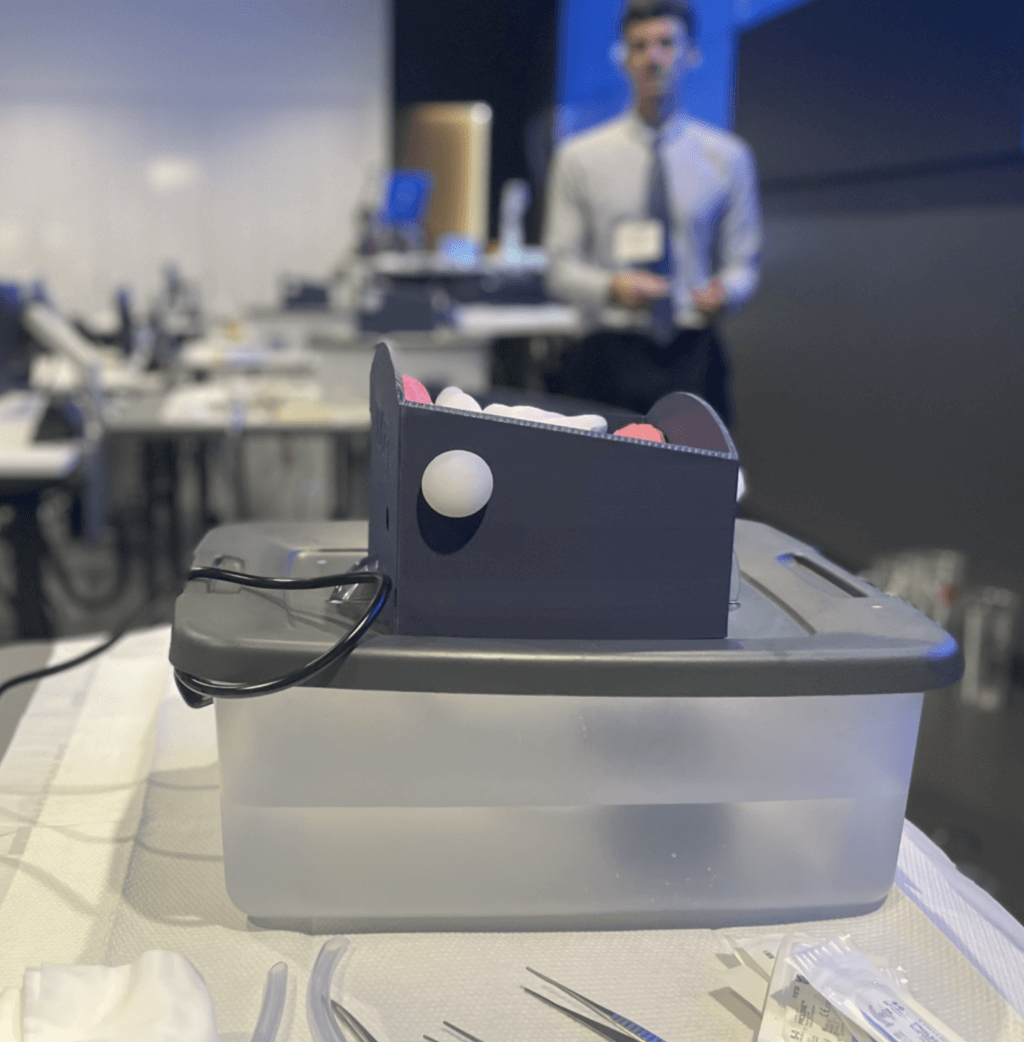

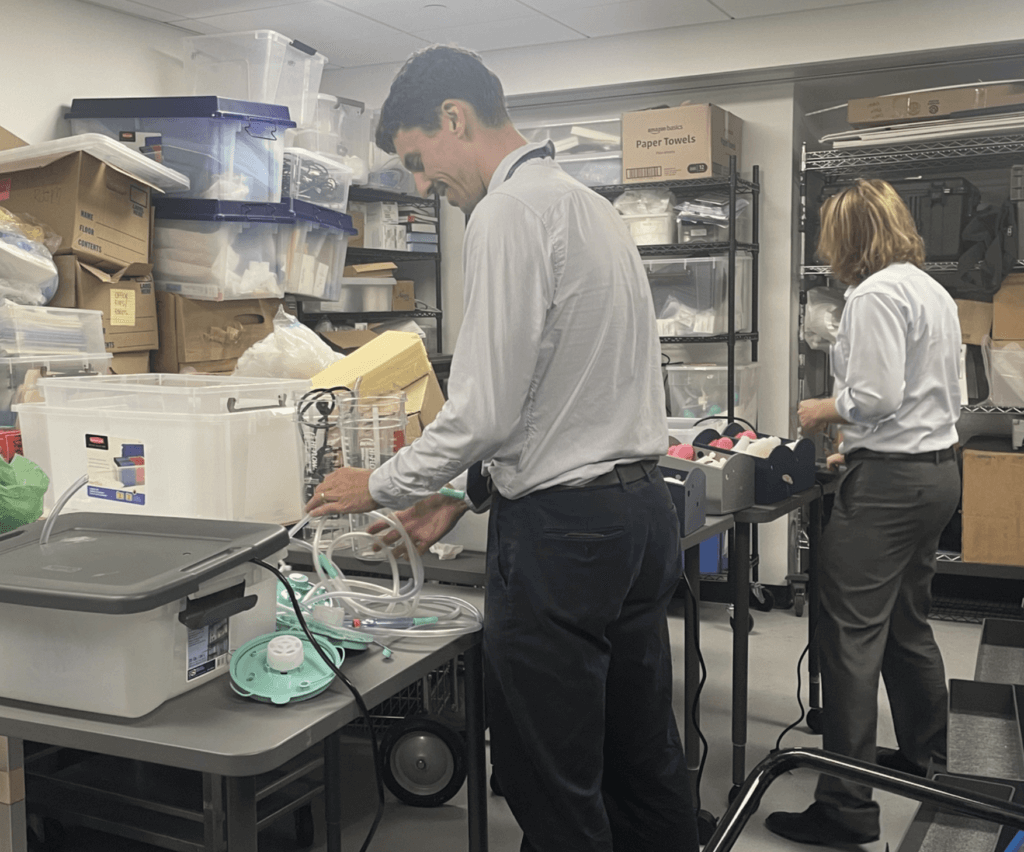

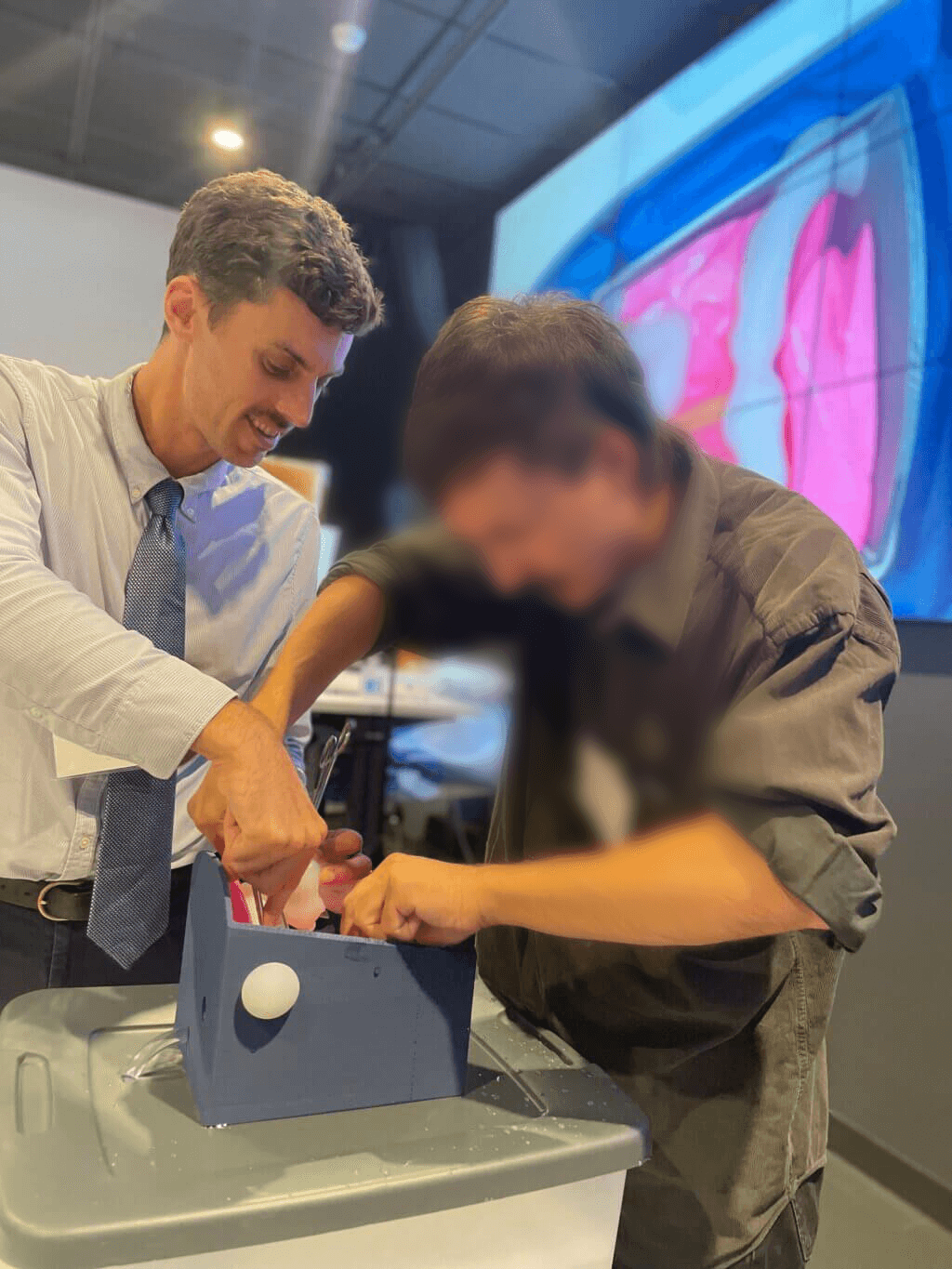

An abdominal hemorrhage simulator. This is a custom model that we use for surgical education. As part of a lesson to teach surgical trainees to deal with massive bleeding, we designed a model that has a blood vessel with artificial blood flowing through it. The model includes a pump, a reservoir, and a custom designed 3D-printed model of abdominal organs that houses the vessel and allows blood to pool. Participants practice stopping the bleeding, exposing and repairing the vessel. Also, this is run as a simulation so that participants also practice non-technical skills teamwork and dealing with stress.

Q: Why did you want to make it?

The origin of this comes from one of our vascular surgeons and surgical educators asking a question: when facing major bleeding, why do some surgical trainees respond too slowly, and how can we address this? We wanted to give surgical trainees a chance to manage the technical and non-technical aspects of major bleeding in a simulation, so that they will be more prepared for the time this happens to them in a real operating room.

Q: What was your process?

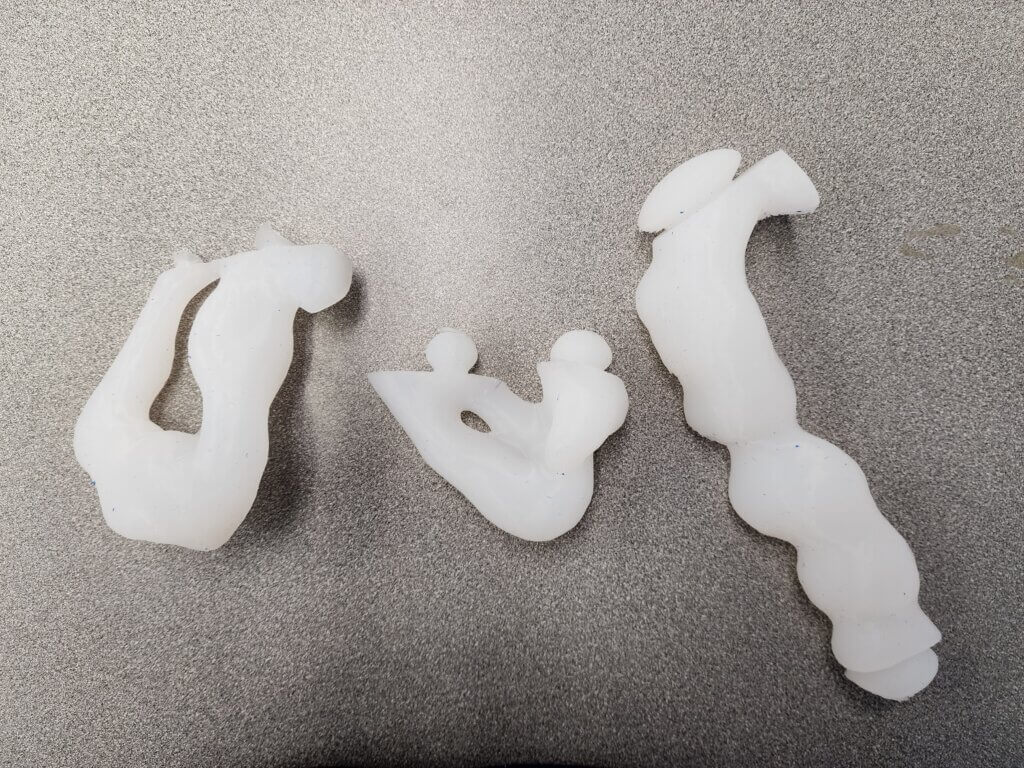

I started by proving that I could build a pumping system for the vessel that would replicate the size and flow dynamics of a large vessel bleeding. I then contacted the Makers Lab and Scott Drapeau designed a fantastic housing for the vessel which has an adequate degree of fidelity. We have a model of the retroperitoneum on which the vessel sits, which is compressible and flexible, and bowel that we made out of silicone, all of which represents the mid-to-right abdomen and the inferior vena cava.

Q: What was the hardest part of the process?

There are two challenging parts. One is making bowel with silicone casts from 3D printed molds. Silicone is really messy and I unexpectedly ruined some clothes.

Next is setting up my models. Each time I prepare for a lesson I take at least 4 person-hours to set up all the components of the model and at least 2-3 more person-hours to break down.

Q: What was your favorite part of the process?

For balance, I have two favorite parts. One is seeing Scott’s design transform from pixels and bytes to a tangible reality via 3D printing. Next is using the model to teach surgical trainees, and watching the participants get excited and a bit stressed out to complete the task.

Q: What do you want to make next?

I want to make a model for a perfused liver to teach the technique for liver resection surgery called hepatectomy. This will involve more fluid dynamics which might benefit from some custom 3D printing to make it work well.