Freeman Bradley grew up in Alabama where, as a young man, he worked in the lab of Dr. George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute. He attended Howard University in Washington D.C. and worked at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland for four years before coming to the Cardiovascular Research Institute (CVRI) at UCSF.

At the beginning of his career at UCSF, Mr. Bradley worked as a technician with Dr. John Severinghaus. In 1957 and 1958, combining technology created by Richard Stow and Leland Clark, they developed the first blood gas two-function analyzer (PCO2 and PO2). The next year, they enhanced the apparatus and presented the first three-function blood gas analyzer that also measured the level of alkalinity or acidity (pH) in blood. In Dr. Severinghaus’s written account of the invention of the blood gas analysis system, he emphasized how his and Mr. Bradley’s invention changed medicine. By the 1960s, their blood gas analysis systems became widely available and proved invaluable in the treatment of severely ill patients. In 1985, an apparatus Dr. Severinghaus and Mr. Bradley worked on was donated to the Smithsonian Museum. This Severinghaus Blood Gas Analyzer is a similar instrument.

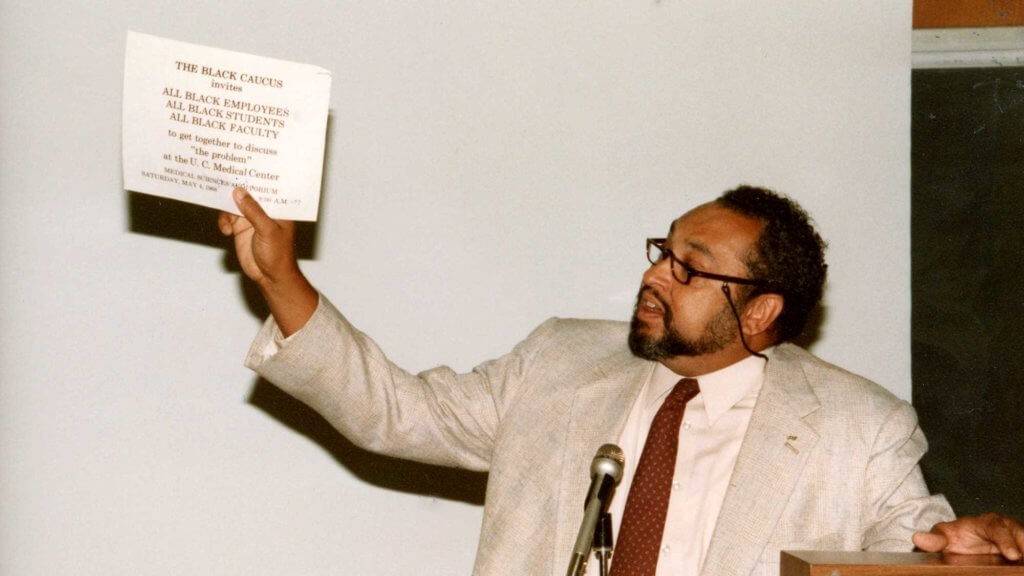

In 1968, Mr. Bradley helped found UCSF’s Black Caucus. He later served as a chairman and frequently represented the Black Caucus in conversations with University administration. In 1977, after 19 years as a postgraduate research physiologist and a specialist in anesthesia research in the CVRI, Mr. Bradley was appointed Director of UCSF’s Research and Development Laboratory. In this position, he oversaw complex and collaborative work that involved imagining new medical technologies and working with electronics technicians, engineers, and instrument makers to bring these technologies to fruition. He was also responsible for fixing these tools when they broke. One of his greatest successes was the design of a neonatal life support and emergency support table. Mr. Bradley also operated his own company, Medical Research Specialties, in San Francisco.

In a 1983 interview printed in Synapse, Mr. Bradley wished for more role models for young Black scientists. The interviewer concluded, “There may be a need for more minority role models, but the character and achievements of Freeman Bradley serve as a model for all people.”