Assessing student understanding is a key component of teaching and learning at UCSF — whether for adapting instruction, providing meaningful feedback, or for accreditation purposes. UCSF is known for being at the forefront of health science research, and academics at the university are no different.

In 2020, the pandemic forced UCSF faculty and staff to rapidly adapt by recreating their classes for virtual learning environments, focusing on new technologies, and delving deeper into resources already available on campus. Stemming from interprofessional and campus discussions during the Committee on Education Technology meetings around adapting instruction in response to COVID-19, this article looks at how academic programs at UCSF have adapted the ways they assess student learning as well as some of the related challenges and goals for assessments in the future.

Diversified assessment opportunities

Faced with disruptive pressures in 2020, different schools at UCSF found their own solutions for facing the challenges of remote instruction. Teaching and support teams mapped the different forms of instruction, didactic or clinical in nature, and focused on finding alternatives for in-person assessment that not only evaluated the same learning outcomes but also utilized the same cognitive processes.

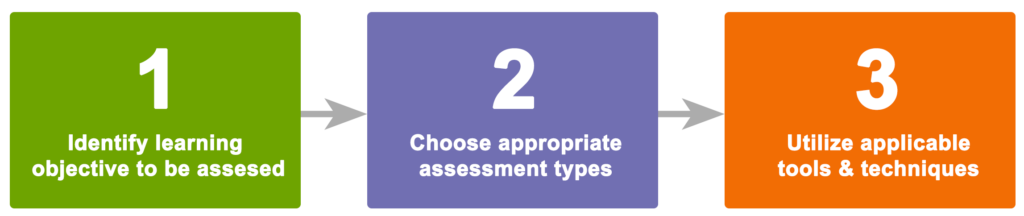

For example, efforts were made to keep physically demonstrable skills aligned with hands-on activities, while didactic learning was predominantly assessed using online assessment including virtual debates, discussion posts, and other means of expression. After identifying appropriate assessment types, teams used the various tools and techniques available to them to make informed instructional design decisions. The following steps were completed sequentially to ensure that the desired learning outcomes directly informed all assessment and technology decisions.

For knowledge-based assessment, the use of the Collaborative Learning Environment (CLE) increased multifold, with an emphasis on the use of targeted quizzes, polls, discussion forums, and other assignment types to give students a range of opportunities to demonstrate their understanding. These activities also provided varied learning experiences by incorporating Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a set of principles for designing a curriculum that aims to provide all individuals with an equal opportunity to learn.

Asynchronous, remote assessments with corresponding rubrics also provided an opportunity for students to practice various skills. For example, Professor Annette Carley RN, DNP, NP at the School of Nursing tasked students with recording how they would present information during patient rounds by giving them targeted rubrics to assess their communication style, engagement, and other skillsets. Similarly, many of the competency-based assessments went virtual, with custom simulations, video physicals, and roleplaying activities being incorporated into the curriculum to help nurture and maintain the high standard of learner proficiency on campus.

Assessing clinical skills

As part of an essential workforce, in-person functions at UCSF continued in varying degrees for both faculty and students. Enhanced safety precautions, such as limiting in-person, clinical time, and reducing intergroup exposure brought forth its own challenges; Creating diverse learner-patient groups and providing students hands-on experience with various faculty proved to be difficult during the pandemic.

The incorporation of telehealth in academia became a mainstay for remote instruction on campus. Learners engaged in telehealth not simply as a temporary workaround, but rather as a vital component of their health science practice going forward.

“We had probably half an hour talk about telehealth pre-Covid, now we have incorporated telehealth in all of our clinical courses. A lot of our students are going out and utilizing telehealth in clinical experiences. Clinical reasoning and integration of telehealth are absolute keepers.”

Theresa Jaramillo, PT, DPT, MS

Associate Program Director & Clinical professor

Physical Therapy Program at UCSF

Assessing students’ telehealth performance and providing active feedback was challenging; Chandler Mayfield and Era Kryzhanovskaya, MD from the School of Medicine noticed an issue of students receiving delayed feedback due to an increased demand for faculty’s time in both their work and personal lives. They also found that changes in maximum capacity and physical distancing in the clinical environment led to less space and time for real-time, face-to-face feedback early in the pandemic. In each case, they strategized to find technology and process solutions that aimed to provide students with more active feedback during these changing environments.

Monitoring learning strategically

The transition of some course elements into an online format helped open opportunities for deeper learning. For example, the Physical Therapy program noted gains in student’s clinical reasoning skills as a result of them having more time to discuss techniques during Zoom sessions than previously available during in-person, lab sessions.

Increased use of the CLE allowed closer monitoring of students’ grades in various assessments and helped identify at-risk students. Staff was also able to monitor how students were interacting with the course content in the CLE and troubleshoot student engagement as needed. The data types and evaluation methods varied from program to program, ranging from using information such as student participation during discussions to using CLE logs to assess how actively students were engaging in course content. The logs also provided analytics such as video view-counts and watch-durations that are now being used to evaluate video performance and inform future modifications.

Some schools were able to use external video content within their course libraries, while others noted a significant increase in the creation of instructional videos and recordings directly by the teaching staff. In each case, teaching staff had to be strategic about the types of videos being shared to ensure that the content was properly curated and cohesive with the other elements of the course.

Looking ahead

One of the takeaways from remote learning has been to provide students with more flexibility in various elements of their course content, including assessments. Allowing students to choose the time and place for taking an assessment, whenever possible, has shown to be favorable for both faculty and students. Schools are continuing to consider different areas where they may be able to provide this flexibility.

“One of the points here is opening up to the flexibility of self-administered exams and being adaptable and innovative to evaluate where else we can offer this flexibility and format change to accommodate a pandemic and various modes of learning & assessment.”

Era Kryzhanovskaya, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of General Internal Medicine at UCSF

The hope is that in addition to increased flexibility, this will lead to what Chandler Mayfield calls a “shift in ownership” for the learner, which in turn will require a balance between exam security and reinforcing learner trust.

Another wish list item that came up during the discussions was the need for data analytics for the vast amount of assessment data that is collected in courses. Whether developing processes for combining spreadsheets or utilizing analytic tools to monitor student progress on various markers, the need for making sense of the vast amount of learning data being collected and reducing the noise within it was one of the goals unanimously voiced during these discussions.

Have questions about designing assessments? For instructional design support and consultations, contact the Learning Tech Group.