Trailblazers in behavioral and developmental pediatrics

Introduction

A relatively new medical field, developmental-behavioral pediatrics came out of an increased demand for mental health services in pediatric care starting in the 1920s. In the mid-twentieth century, as infant and child mortality rates declined, pediatricians and those engaged in early childhood development research became increasingly interested in understanding and treating behavioral problems and developmental delays. By the 1960s, there was an uptick in diagnosing and treating psychosocial problems among children and in promoting their success and happiness – both central tenets of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Drs. Leona Mayer Bayer, Helen Fahl Gofman, and Hulda Evelyn Thelander, and Ms. Selma Fraiberg and Ms. Carol Hardgrove were pioneers in this field; however, their influence and involvement have been largely overlooked. Collectively, they made significant contributions to treating children with learning differences and complex healthcare needs, training health professionals, promoting disability rights, understanding infant mental health, promoting the importance of unstructured play in early childhood development, and championing for the inclusion of families and parents in pediatric care.This primary source set brings visibility to a hidden collection of these women’s correspondences, diaries, memoirs, travel accounts, medical manuscripts, and research notes.

As women in the field of medicine, they were trailblazers. They carved out their own careers while championing the integration of child psychiatry and education theory and practice into pediatrics. These women also were indoctrinated into fields that were fierce promoters and contributors to gender norms, heteronormativity, gender discrimination, anti-Black racism, racism, and ableism. The women pioneers featured here were white. Both Dr. Gofman and Ms. Selma Fraiberg were Jewish. Drs. Bayer and Thelander and Ms. Hardgrove were not. Drs. Bayer, Gofman, and Thelander learned medicine at institutions that were predominately white (PWIs) and patriarchal.

This primary source set brings visibility to a hidden collection of these women’s correspondences, diaries, memoirs, travel accounts, medical manuscripts, and research notes. In bringing this material together, the goal is to demonstrate and document these pioneers’ impressive achievements, accomplishments, and great skills as influencers in medicine. Access to these collections will not only allow for a deeper exploration of their contributions to the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics,but will also sheds light on the inner workings and epistemologies of twentieth-century pediatric research, theory, and practice.

Leona Mayer Bayer correspondence, 1945-67, MSS 86-54

In 1928, Leona Mayer Bayer (1903-1993) received her medical degree from Stanford University Medical School as one of five women of her class of sixty students. Upon graduation, she began a clinical appointment at Stanford University Hospital in San Francisco as an internist specializing in endocrinology. During her tenure, Dr. Bayer was affiliated with its Endocrine Clinic and co-chaired a youth clinic for patients 13 to 19 years of age. From 1938 to 1950, Leona was a research associate at the Institute of Human Development (IHD) at University of California, Berkeley (UCB). She conducted physical examinations on Berkeley Growth Study participants. Her IHD contract was not renewed due to her refusal to sign UCB’s “Loyalty Oath.” Bayer became known as “the woman who would not sign.”

Dr. Bayer was a life-long activist. She supported the anti-fascists during the Spanish Civil War, was an active member of the San Francisco’s Branch of Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, demonstrated against the Vietnam War, opposed the nuclear war arms race, and was an active member of the Sierra Club. Her activism extended into her professional life. In 1939, she and her husband, Dr. Ernst Wolff, opened a practice to treat children from low-income families. In 1953, they founded a center for children with developmental delays which was later incorporated by the Pacific Medical Center. They also held leadership roles in the World Health Organization (WHO) and the California and San Francisco Mental Health Associations.

Bayer and Wolff retired together in 1969; however, Leona returned to UCB’s IHD in 1970 and was involved in its intergenerational studies until 1980. During this time, she also played an active role in the reemergence of the Bay Area chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) and was awarded the PSR Broad Street Pump Award in 1987 for her efforts. She died at her home in San Francisco in 1993 at the age of 90.

What makes her a pioneer in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics?

Dr. Bayer was a progressive thinker and endocrinologist, which was a male dominated field during her career. Dr. Bayer was an early adopter of hormone therapy to address culturally deemed abnormal stature in children. While not typically considered part of developmental-behavioral pediatrics, growth hormone therapy espoused similar core tenets and considerations, most notably a gendered body-mind connection. Throughout her career, Dr. Bayer championed psychosomatic medicine – the belief in a relationship between psychological health and physical development. She is most remembered for her pioneering work in the field of growth studies/anthropometry that focused on the relationship between endocrine metabolism, statue, and personality/psychology.

Dr. Leona Mayer Bayer Correspondence digital collection on Calisphere

The Bayer documents are mostly from the 1940s and early 1960s. Content includes early correspondences between Bayer and pharmaceutical companies; requests for talks on her research on the relationship between endocrinology, stature, and sexuality; and professional messages on promoting psychosomatic medicine, and collaborating with Nancy Bayley on a book titled, Growth Diagnosis: Selected Methods for Interpreting and Predicting Physical Development from One Year to Maturity.

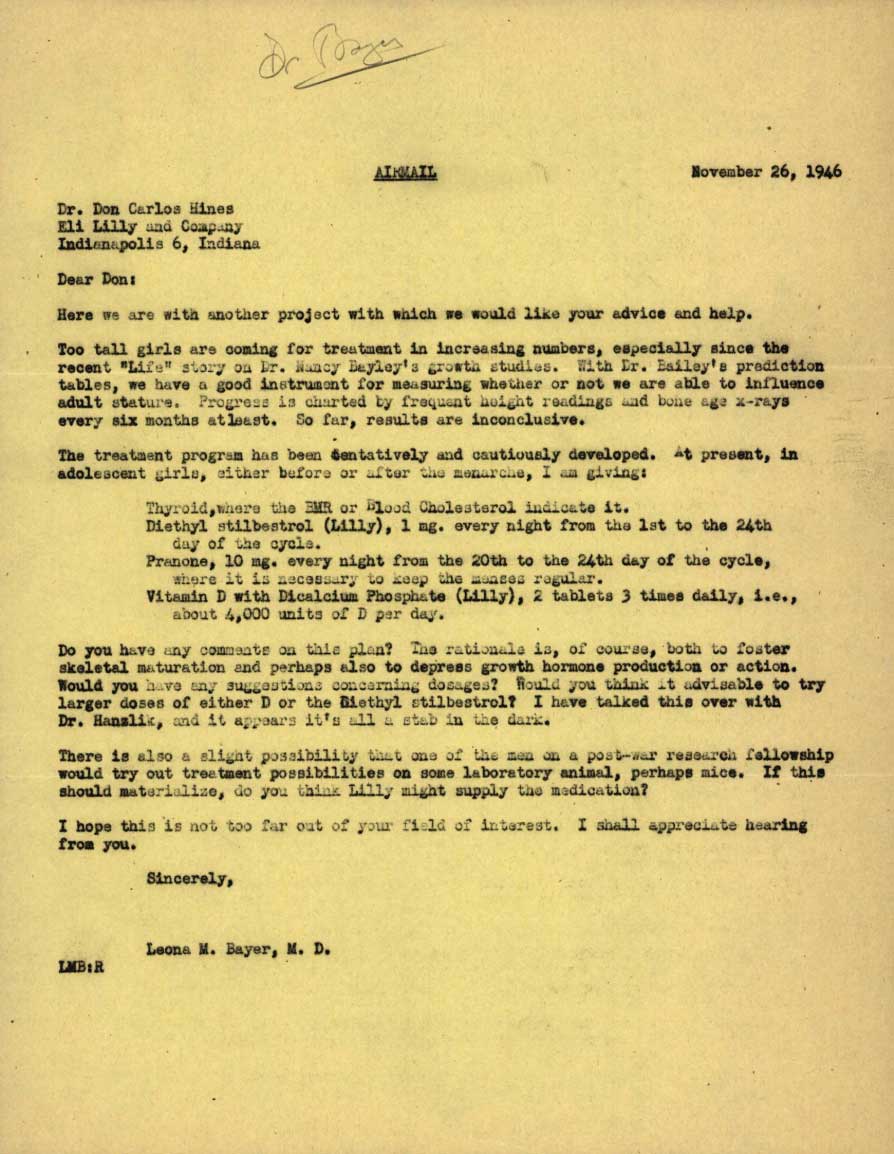

Letter from Dr. Bayer to Dr. Don Carlos Hies of Eli Lilly and Company

Page 41 of 83

November 26, 1946. Reporting a recent increase “too tall” girls seeking treatment due to a recent Life Magazine article on growth prediction, Bayer asks for clarity on recommended pharmaceutical regimens for adolescent girls.

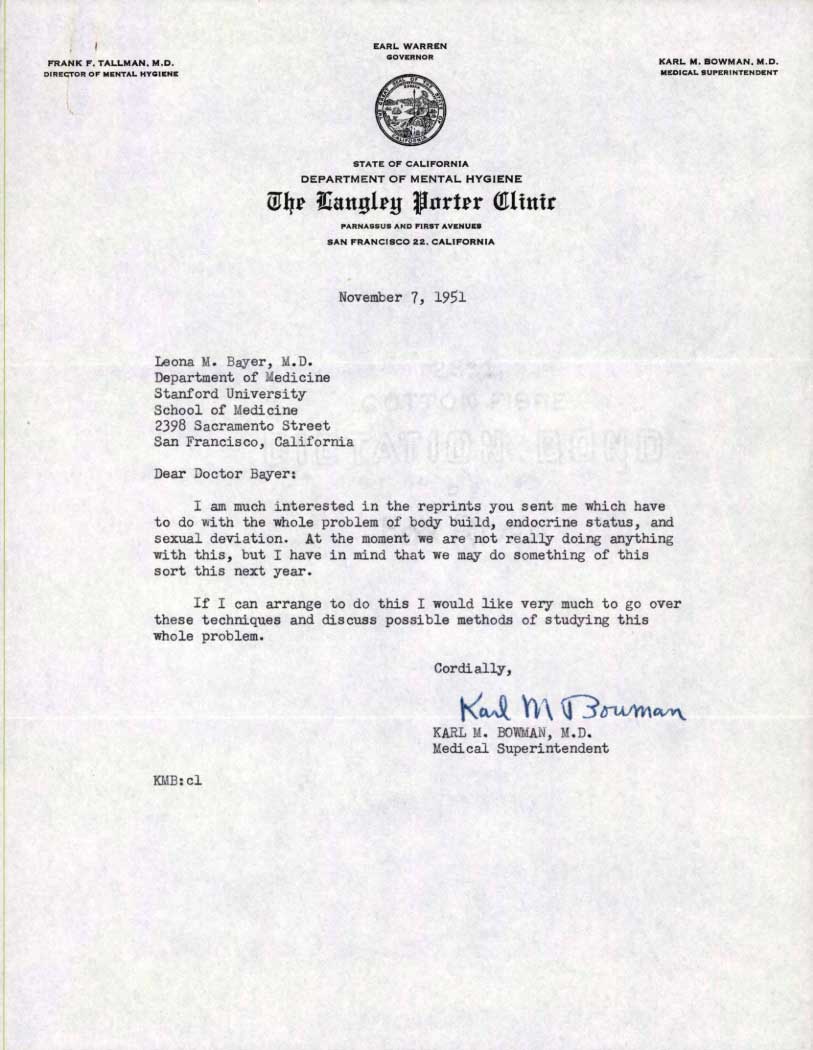

Typed letter from superintendent of The Langley Porter Clinic, Dr. Karl M Bowman to Dr. Leona Bayer

Page 24 of 38

November 7, 1951. Bowman responding to Bayer sending him her article on “somatic androgyny.” In 1950, UCSF’s Langely Porter Clinic became the administrative headquarters for research funded by the state-level Sexual Division Research Act.

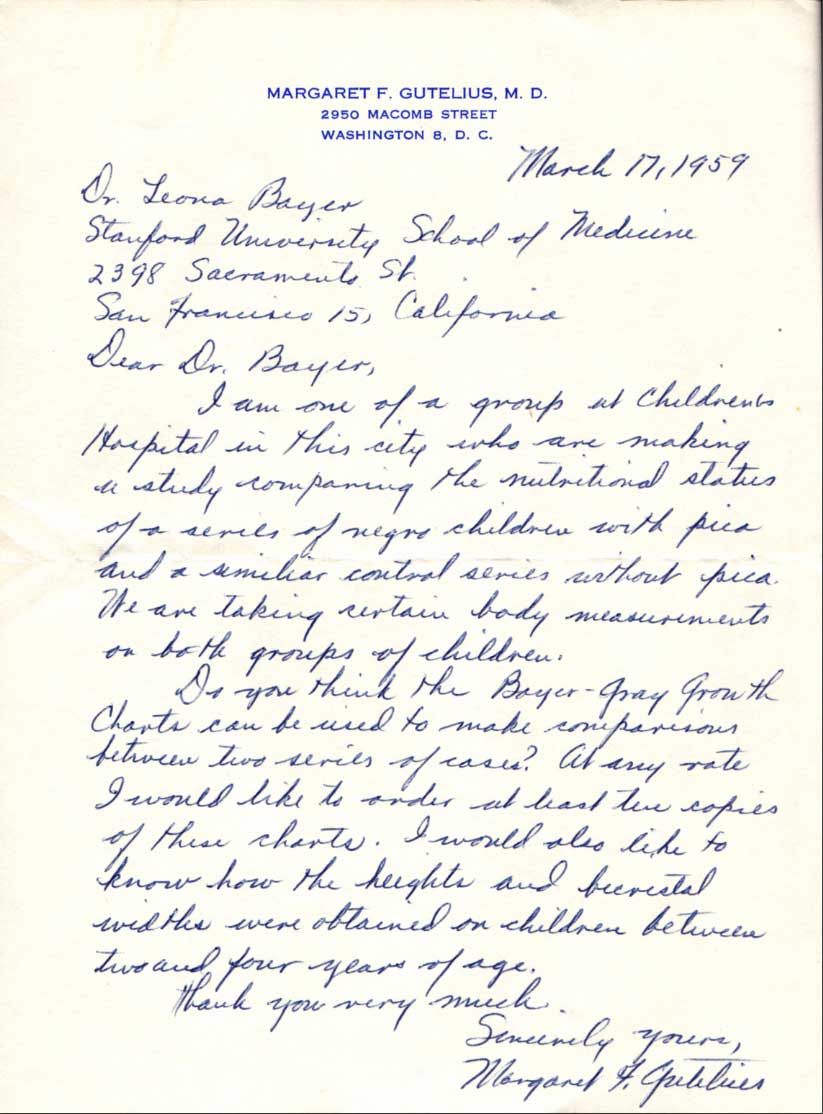

Handwritten letter from Dr. Margaret F. Gutelius to Dr. Bayer

Page 56 of 61

March 17, 1959. Gutelius asked Bayer for copies of the Bayer-Gray Growth Charts so she could compare body measurements of a group of Black children with pica with a group without. [Caution: outdated and offensive wording used when identifying race of children].

Key contributions

Prescribed growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen to disrupt growth patterns in favor of culturally accepted heights – Starting in the 1930s, pharmaceutical companies supplied doctors with the growth hormone and testosterone to treat short children and her synthetic estrogen (DES) to stop “too tall girls” from growing taller. This form of growth promoting therapy was later found ineffective. Eventually, estrogen therapy for tall girls ended as DES was banned in the United States as it was found to cause cancer.

Conducted research on possible connections between endocrine metabolism, psychological state, and the physical body – In a 1946 article published by the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, Bayer and her collaborator Nancy Bayley suggested that “somatic androgyny” may relate to same sex orientation. Many people found this idea interesting, members of the Mattachine Society’s Bay Area chapter (an organizing group during the early period of LGBTQIA+ activism) who hosted a talk by Bayer in1957.

Developed a formula to predict stature with growth specialist Nancy Bayley – Dr. Bayer was fascinated by the possibility of predicting adult size and comparing growth rates with perceived norms. In 1959, University Chicago published Bayley and Bayer’s book on growth diagnosis and prediction. In it they coined the term “growth diagnosis” to mean how a child’s status and maturity compares to “specific norms,” and how they proposed a possibility for predicting adult size.

Gofman (Helen Fahl) Papers, MSS.2014.17

Dr. Helen F. Gofman (1917-2004) was born at home in Ohio. She received her AB (1939) at Oberlin College. While at Oberlin she met her future husband Jack Gofman. They married in 1940, the same year she earned her MA in Biology at Case Western University. They move to California where Helen began the Anatomy PhD program at University of California, Berkeley (UCB). In 1941 she left UCB and started medical school at UCSF. She received her MD in 1945 and completed her residency in pediatrics in 1947. She remained at UCSF throughout her entire career where she held multiple positions, including instructor (1953-57), Medical Director for the Pediatric Reading Therapy Program (1962-69), Pediatric Reading and Language Development Clinic (1966-83), Assistant and Associate Professor of Pediatrics (1957-64 and 1969-83), and, most importantly, Director and Co-Director of the prestigious Child Study Unit (CSU) (1967-73,1978-83). Throughout her career and in retirement, she gave over 300 presentations and was a prolific researcher and published author.

Dr. Gofman was passionate and knowledgeable about health and well-being in general. Although trained as a pediatrician, her interests in health and healthcare stretched beyond this specialty. In the 1950s, she co-authored a book on heart disease and diet, Low Fat, Low Cholesterol Diet. The first edition’s (1951) book jacket identifies Helen as a physician and housewife. Low Fat, Low Cholesterol Diet was reprinted and revised multiple times, contributing to the prevailing eating doctrine for decades that all fatty food was bad and dangerous and low-fat foods were good and healthy.

Dr. Gofman continued to champion health and healthcare causes well into retirement. During the 1990s, she was an outspoken critic of the HMOs (Health Maintenance Organization) Revolution of healthcare and Medicaid reforms. She passed away at the age of 87.

What makes her a pioneer in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics?

With a career spanning close to forty years, Dr. Gofman was referred to as “the continuous thread” for the introduction of behavioral pediatrics at UCSF. As director and co-director of CSU, Dr. Gofman oversaw one of the first and longest lasting training programs in behavioral pediatrics in the US. She published and gave talks on a wide range of topics addressing differences in learning including, motor testing and development, reading difficulty, children in divorce, hyperkinesia, diet and behavior, dyslexia, learning disorder, language disorders, and school phobias. Learning differences was her areas of focus.

Dr. Helen Fahl Gofman Papers on Calisphere

The Gofman collection documents the life and work of Dr. Gofman. Materials include writings, lectures, correspondence, publications, research materials, working files for individual patients (children), diagnostic tools and tests, photographs, slides, audio-visual recordings, and biographical materials. Some material pertains to her own campaign to bring attention to the compromise of care occurring with the rise of HMO’s and the harmful changes with Medicaid.

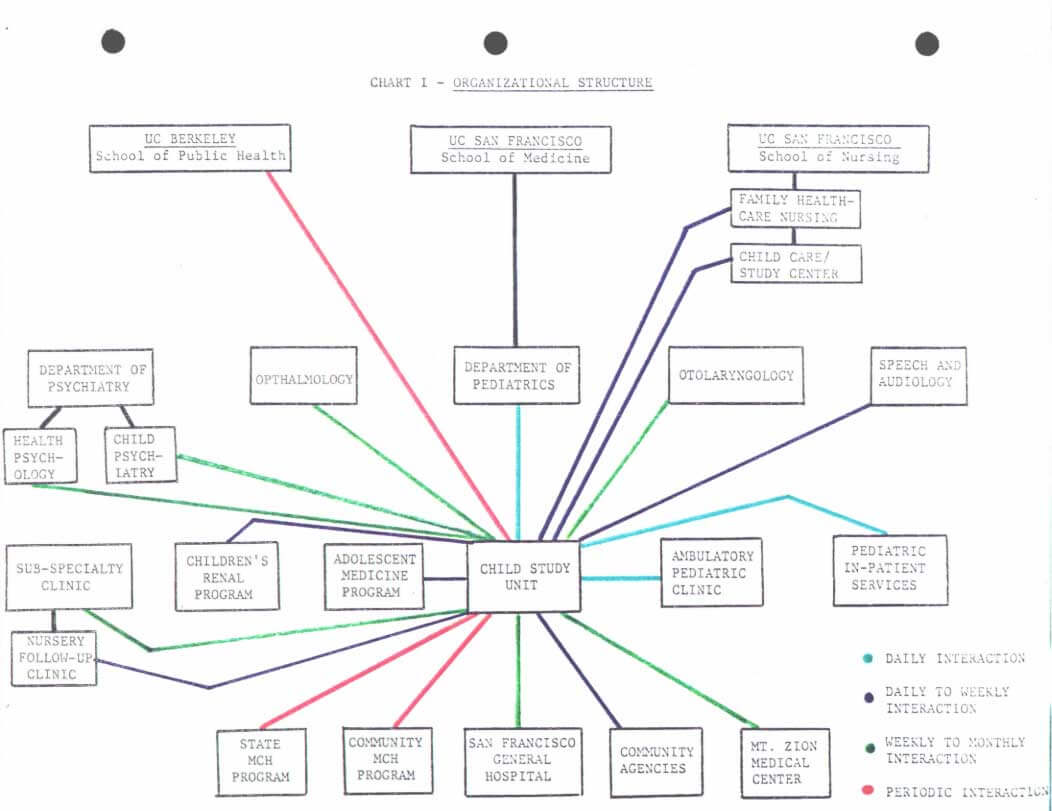

Chart I: Organizational Structure

Page 24 of 189

Helen Gofman, CSU’s renewal application for Training in the Behavioral Aspects of Pediatric Health, “Chart I: Organizational Structure,” 1982-1983. Chart depicts CSU’s relationships with other healthcare services.

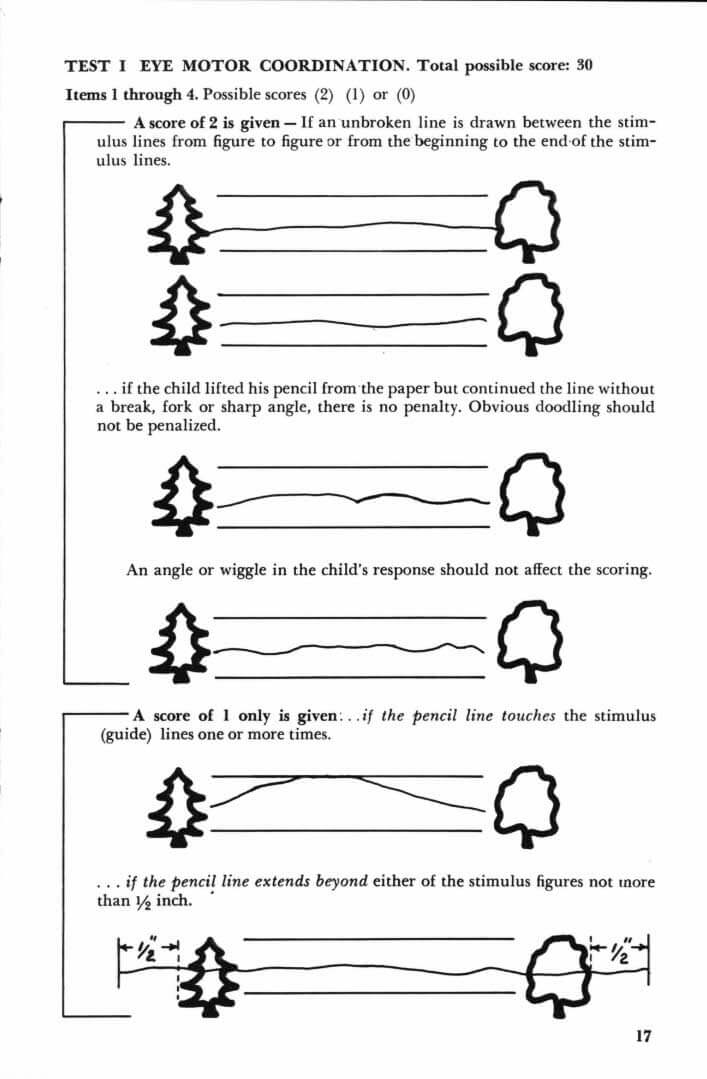

Eye Motor Coordination test

Page 27 of 392

Marianne Frostig, et. al, “Test I Eye Motor Coordination,” from Administration and Scoring Manual: Developmental Test of Visual Perception (DTVP), 1964. UCSF’s Learning and Language Disabilities Research Clinic recommended the use of this test to evaluate school readiness of children 4-9 years old. In this section, evaluators were instructed to mark children down for “wiggly” lines and “obvious doodling” when assessing eye motor coordination. A newer version of DTVP is in use today.

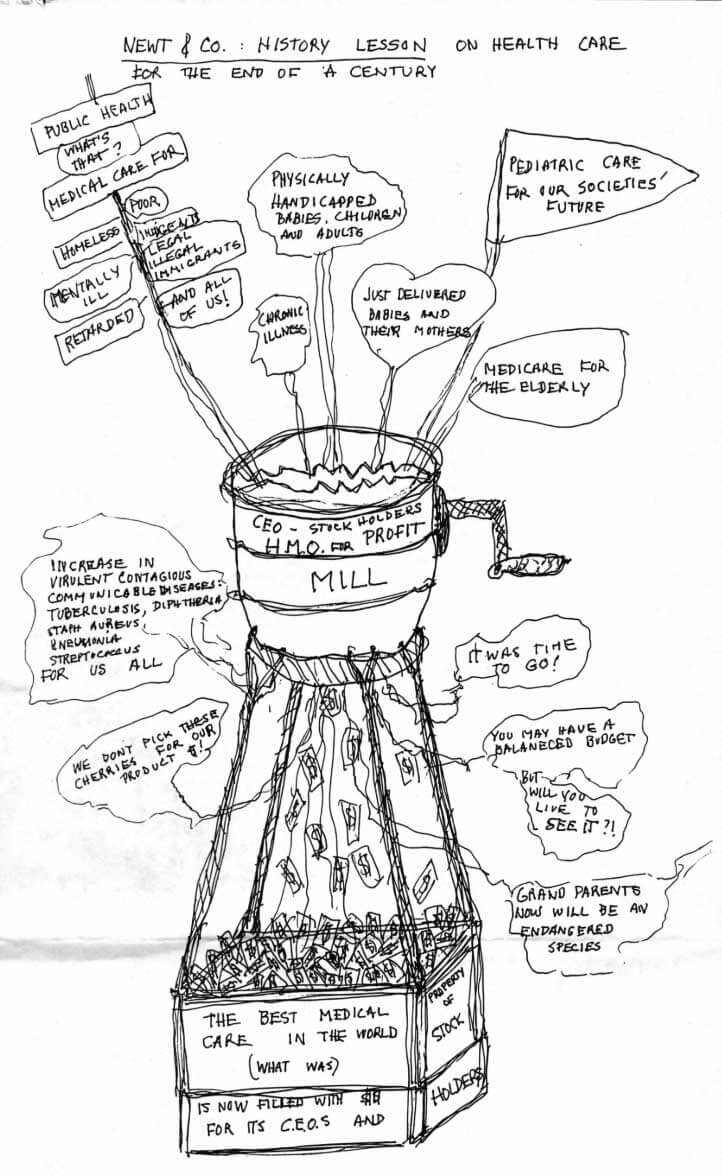

Political cartoon

Page 7 of 13

Helen Gofman, “Newt & Co: History Lesson on Health Care for the End of a Century” c. 1994. In her political cartoon, Gofman depicts a HMO (Health Maintenance Organization) as a mill grinding health issues for corporate profit. She refers to House Speaker Newt Gingrich and his followers as Newt and company and forecasts an increase in contagious diseases because of the HMO takeover.

Key contributions

Supervised the iconic Developmental-Behavioral Child Study – Beginning as the Pediatric Mental Health Unit, CSU evolved and branched out to include the Pediatric Reading Therapy Program, Pediatric Reading and Language Development Clinic, and its Learning and Language Disorder Program. Dr. Gofman championed the notion that pediatricians should recognized disabilities in their patients to create opportunities for interventions that would enable children to live happy and successful lives. To gain experience, pediatricians would rotate through CSU.

Managed the Learning and Language Disabilities Research Clinic – Under Gofman’s supervision (1965-1972), physicians were trained in studying children who fared poorly in school due to unspecified reasons. Gofman’s clinic conducted research in Minimal Brain Dysfunction (MBD), Developmental Dyslexia, Specific Learning (Disability) Disorders (S.L.D.) and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). While diagnosis and treatment of learning and language differences mainly occurred in school settings, this clinic offered much sought out findings on the effectiveness of learning accommodations by studying children.

Spoke out against HMOs and Medicaid Reform in the 1990s – “[A]larmed to see our medical care put in the hands of profiteers who know little about what good medical care entails,” Dr. Gofman sketched political cartoons, wrote letters to the editor, and created collages to draw attention to what she saw as the growing injustices in healthcare due to HMO’s and Medicaid reform. Gofman felt protocols developed by HMOs were motivated by profit and not care.

Hulda Evelyn (Jo) Thelander papers, 1935-1987, MSS 89-67

Hulda Evelyn (Jo) Thelander (1896-1988) grew up in Little Falls, Minnesota. She trained as a nurse during WWI and received philanthropic funding after the war to attend medical school where she was one out of twelve women (55 total students). She received her B.A. (1922) M.A. (1923) and M.D. (1925) from the University of Minnesota. After graduating, she interned at Children’s Hospital in San Francisco and in private practice with Dr. Fleischner (Chief of Pediatrics) and Dr. Edward B. Shaw. In 1926, she traveled to Rockefeller Institute’s pediatric clinic in China for a fellowship, but her time was cut short due to political instability. Returning to SF, she re-joined Dr. Shaw’s private practice and became a UCSF Pediatrics faculty member. During her tenure at UCSF, she was the Chief of Pediatrics for 10 years and Chief of Staff at SF Children’s Hospital for two terms. During WWII, she served as a commissioned Lt. Commander in the Navy, the first woman to achieve this rank through commission. Thelander continued to treat women veterans until 1953.

Dr. Thelander was a prolific researcher of children with disabilities and of women in medicine. After WWII, she collaborated on a study of 230 married and unmarried women physicians and found married women often sacrificed their careers for family duties. Jo never married or parented children.

She held various roles and received several awards throughout her career and in retirement. Roles including a diplomate of the National Board of Medical Examiners. Dr. Thelander received numerous awards, most notably the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Award for her work with children living with disabilities.

Jo retired in 1967 and returned to medical school in 1968-1971. In retirement, she continued to advocate for children with disabilities and offered safe spaces for women in medicine to talk about challenges and share resources. Dr. Thelander passed away in 1988. She was 92.

What makes her a pioneer in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics?

In 1952, Dr. Thelander’s Child Developmental Center at San Francisco’s Children’s Hospital opened. It comprised of a nursery and a center for children with “birth defects”. Under her 15-year direction, the Center provided diagnosis, total evaluation, therapy, family counseling, instruction, and reevaluations to patients and their families. It also conducted research on children living with disabilities. This approach to treating pediatric patients with complex health needs and their families inspired hospitals across the US to establish centers of their own.

Thelander (Hulda Evelyn) Papers, digitized collection on Calisphere

The Thelander collection consists of newspaper clippings, ephemera and planning correspondences documenting her extensive travel, award announcements, certificates and awards, conference pamphlets, her lecture notes and slides, photographs, detailed descriptions of physical spaces and programs housed in the Child Development Center, descriptions of diagnosis and treatment plans for children with complex healthcare needs, bibliographic references, journal article reprints with personal notations, and statistical reports.

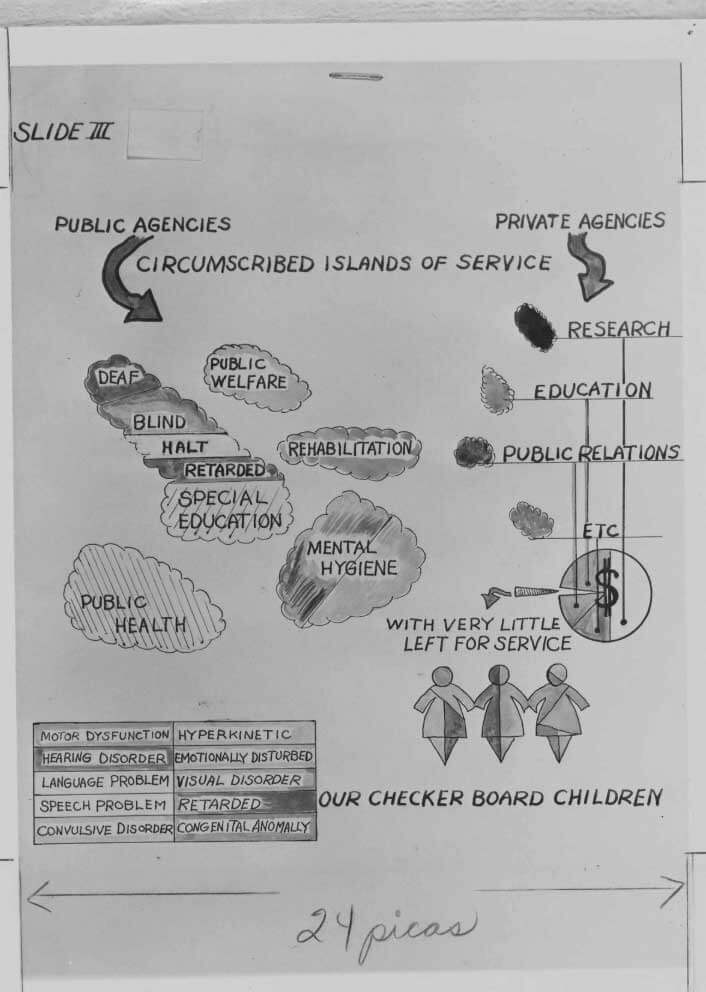

Presentation slide about funding

Page 8 of 159

Child Development Center Redevelopment Plan Presentation, “Slide III,” c. 1974. This slide depicts how services for children with learning and mental differences seldom receive funding from public and private agencies intended to support them.

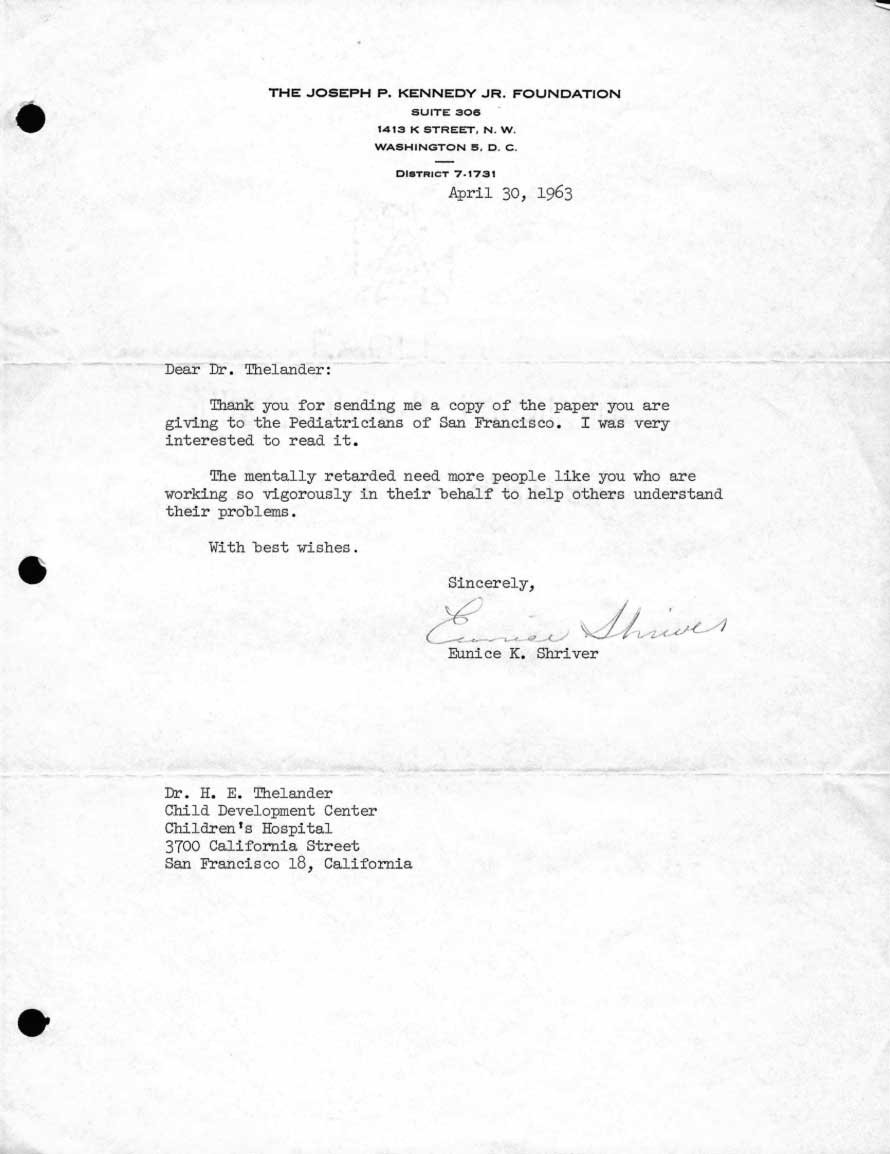

Typed letter from Eunice K Shriver

Page 103 of 108

Typed letter from Eunice K Shriver to Dr. Thelander thanking her for her advocacy, April 30, 1963. Dr. Thelander advocated for people living with disabilities throughout her career and in retirement.

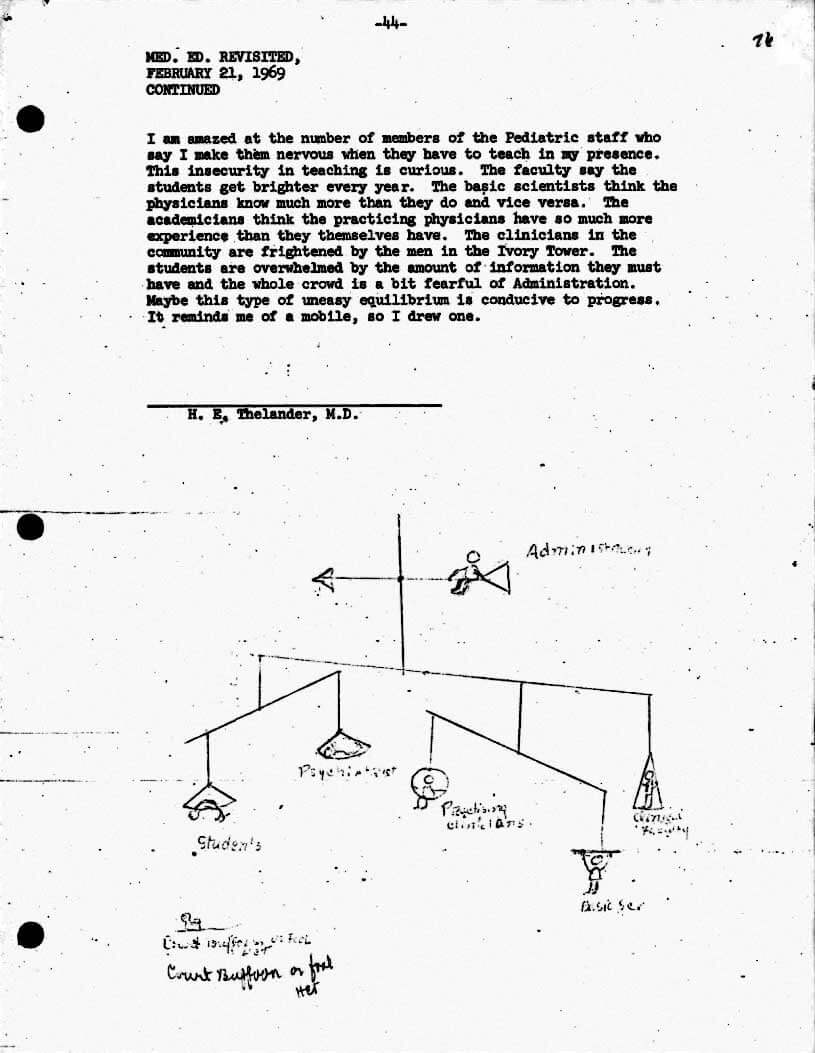

Drawing of a mobile

Page 89 of 281

Jo Thelander, drawing of a mobile depicting an “uneasy equilibrium” that “might be conducive to progress,” Medical Education Second Time Around Diary, February 21, 1969. This sketch is based on how numerous people - pediatric staff, faculty, students, and clinicians - shared their feelings of insecurities in medical education with Dr. Thelander while she was in medical school at UCSF.

Key contributions

Established the Child Development Center at the Children’s Hospital of San Francisco – The Center’s goal was to treat children with disabilities and their families humanely and effectively. It hosted various research studies during her tenure, including studies on children with growth patterns of children with Turner’s syndrome, twin studies, and prenatal antecedents of birth injuries. Thelander saw the Center as an anecdote to the growing biomedicalization of pediatrics and believed in the importance of studying human development.

Advocated for children living with disabilities –Thelander advocated for legislation and programs intended to support children and adults living with disabilities. She was called on by legislators at all levels, including Governor Edmund Brown, to help lead policy efforts. She also collaborated with activists and organizations, including Center for Independence of Individuals with Disabilities (Center for the Handicapped) and Helpers Community Inc (Helpers of the Mentally Retarded).

Attended medical school a second time (1968-1971) –During her second time as a medical student, Thelander recorded her student experiences at UCSF including her reflections on the Black Students Union and Black caucus, sit-ins, student “gripe sessions,” the curriculum, low morale among much of the faculty, student activism around “humanizing medical education,” conversations among women faculty and students, student concerns about the UCSF’s possible involvement in the Vietnam War, and what she saw as a proliferation of drug use among young people.

Selma Fraiberg

Selma Fraiberg (1918–1981) was born in Detroit, Michigan where she received her BA (1940) and master’s in social work, MSW (1945) from Wayne State University (WSU). While in college, she met then teaching assistant Louis Fraiberg who she later married (1945). Selma received additional psychoanalytic training from Richard and Editha Sterba at the Detroit Psychoanalytic Society and Institute (DPSI) a controversial training at the time as the American Psychoanalytic Association prohibited such instruction of non-physicians.

Teaching took up the early years of Ms. Fraiberg’s career. According to a 2018 article by Joel Kanter, Ms. Fraiberg taught classes on “mental hygiene” and case work at the University of Michigan’s School for Social Work (1947-1952) where she also worked as a field supervisor for the university’s Fresh Air Camp. She created and taught a course on human behavior at WSU (1953-1954).

In 1956, the Fraibergs adopted a baby girl, Lisa. Selma was a stay-at-home mom while she wrote her pioneering work on early childhood development, The Magic Years. From 1958 to 1962 she was an associate professor of social work at Tulane University. She also taught MSW students at Smith College for several summers in the 1960s.

A prolific writer and dedicated teacher, Ms. Fraiberg taught child psychoanalysis at the University of Michigan Medical School (1963 to 1979) and was the Director of the Child Developmental Project in Washtenaw County. She wrote several seminal works on childhood development and infant mental health and trauma. Her work on intergenerational transmission of trauma as described in her landmark publication “Ghosts in the Nursery” was groundbreaking. In 1979, Ms Fraiberg opened and directed an infant-parent program at San Francisco General Hospital and was appointed professor of child psychoanalysis at UCSF. In 1981, she was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor and died shortly thereafter. She was 63.

What makes her a pioneer in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

According to her 1981 New York Times obituary, Selma Fraiberg was an authority of early childhood. She helped found the field of infant mental health, Infant-Parent Psychotherapy (IPP), and played a key role in developing mental health treatment for infants, toddlers and their families. Her seminal work, The Magic Years, is still in use in childhood development studies and early childhood education.

Fraiberg (Selma H) Papers on Calisphere

The Fraiberg collection includes manuscripts of books and articles, photographs, reprints of journal articles and pediatric pharmaceutical advertisements (Tranxene for anxiety), research projects plans and budgets, correspondences (many about her work), shared case notes, bibliographies, material from psychoanalysis and adolescent mental health conferences and workshops. Highlights include chapter drafts from Insights from the Blind, correspondences from psychoanalytical training centers, and evaluation scales.

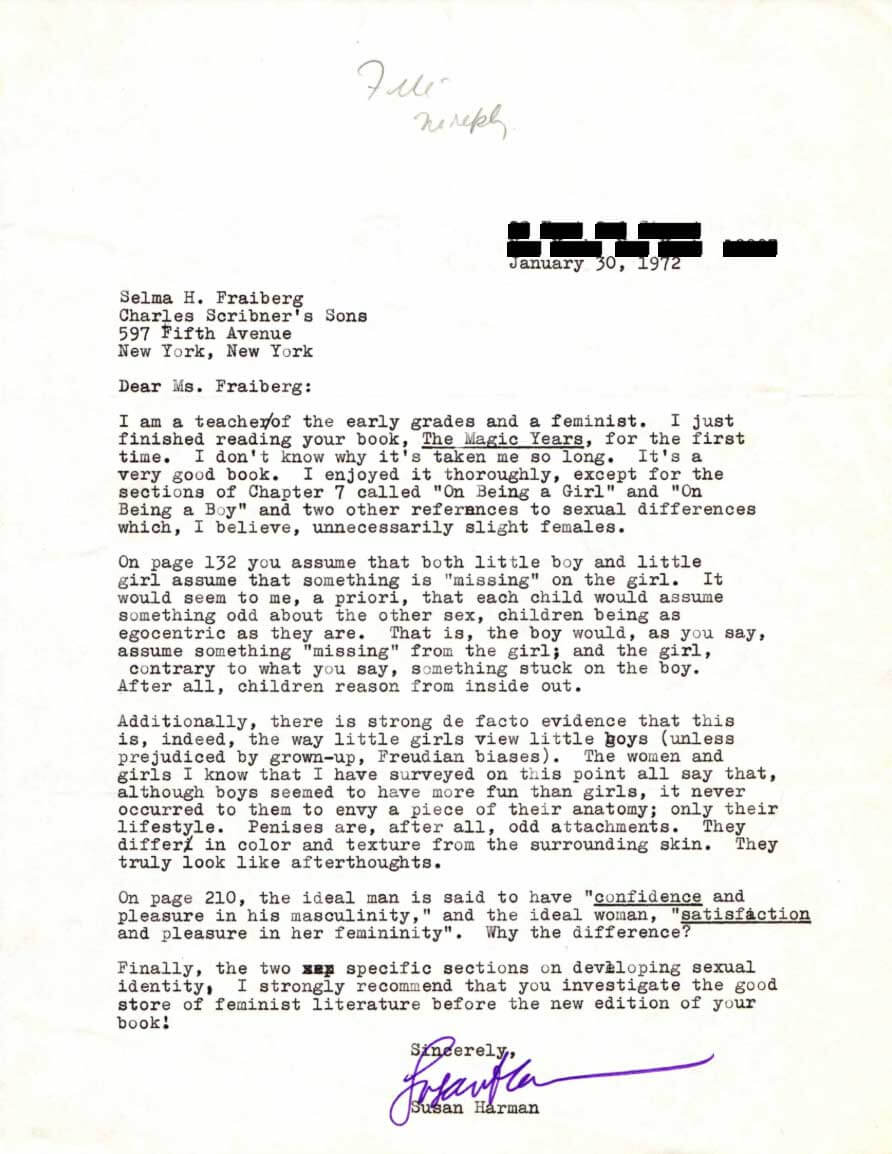

Susan Harman writing to Selma Fraiberg

Page 59 of 86

Typed letter, Susan Harman writing to Selma Fraiberg after reading The Magic Years, January 30, 1972. Identifying herself as a teacher and feminist, Harman questions Fraiberg’s assumption of girls being envious of boys and recommends she rethink her interpretation and check out some feminist literature before updating two sections on sexual identity for the next edition of The Magic Years.

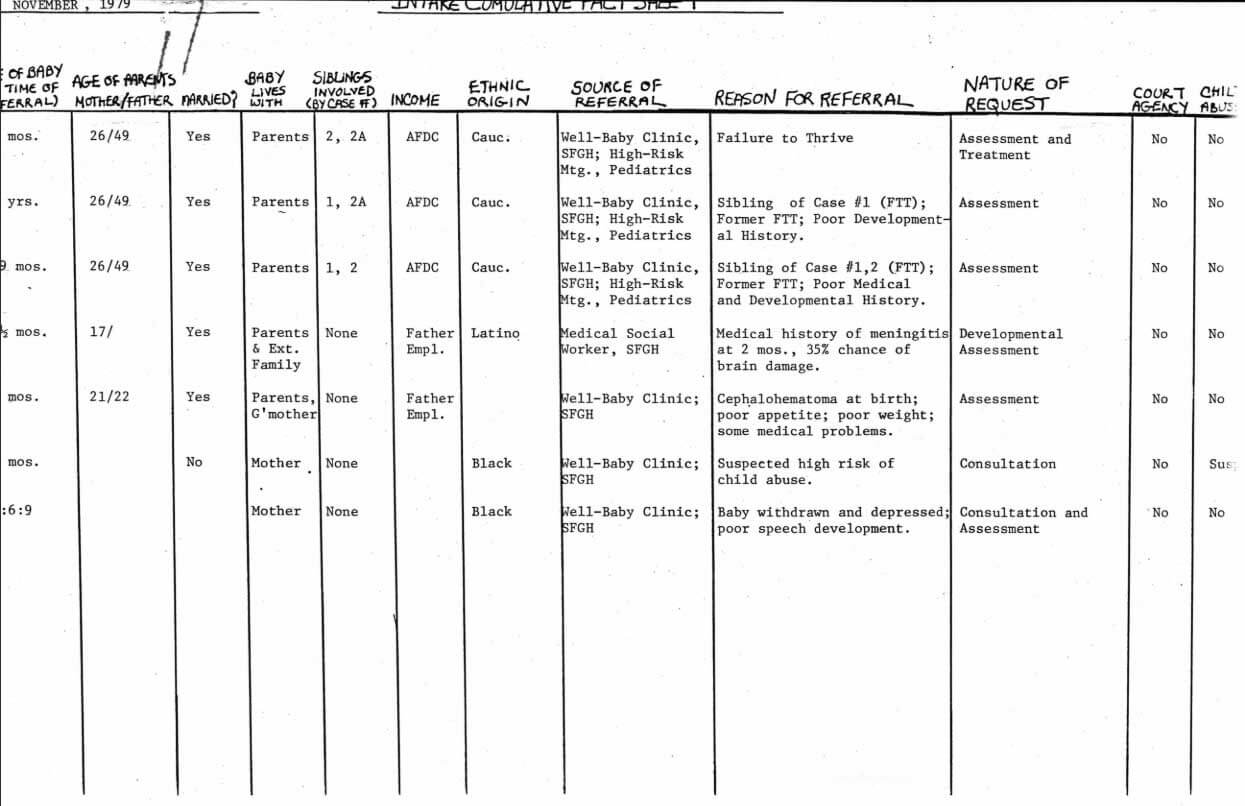

Infant-Parent Program intake sheets

Page 1 of 37

Intake Cumulative Fact Sheets Infant-Parent Program at SFGH,” November 1979-November 1980. Data recorded includes child’s sex, age at reference, parents’ marital status, patient resides with, case number of siblings, income source, ethnic origin, referral source, presenting problem, service requested, legal agency involved, and child abuse. This program employed a IPP approach to treating infant and child mental health. [Caution: these documents include disturbing data and out-of-date depictions of patients]

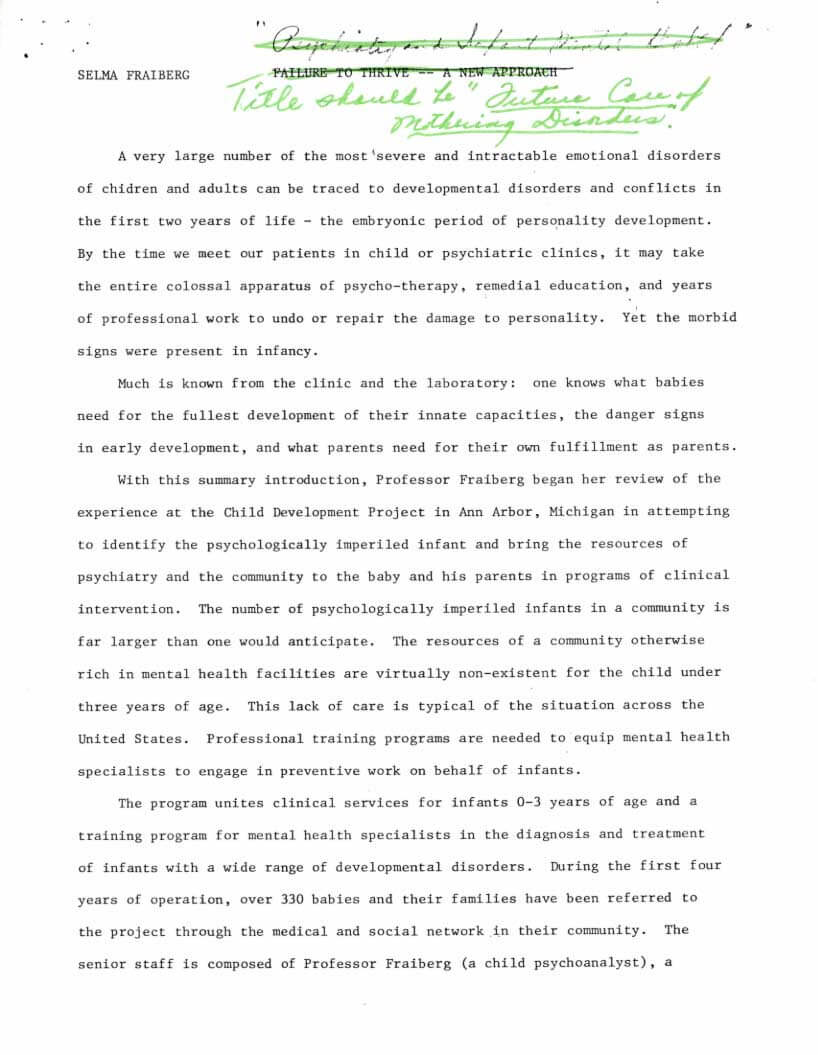

Corrected draft of paper

Page 27 of 41

Selma Fraiberg, Corrected draft of paper submitted to Dr. Marshall H. Klaus at Rainbow Babies & Childrens Hospital, May 18, 1978. In green marker Selma Fraiberg changes paper title to “Future Care of Mothering Disorders,” an editorial testament to her belief in intergenerational trauma.

Key contributions

Championed a psychoanalytical approach to understanding early childhood development – Fraiberg was a supporter and meaningful contributor to the psychoanalytical doctrine in developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Her book, The Magic Years: Understanding the Problems of Early Childhood was very popular and received rave reviews. The title references how a child (0-6) interprets life without reason but rather magical thinking. Fraiberg, like other psychoanalysts at the time, interpreted early childhood as a time when a child becomes “civilized.” In the book, she offers psychoanalytical interpretations about feeding, talking, gender identity, and daily tasks.

Pioneer in Infant mental health – According to Dr. Alicia F. Lieberman, professor of psychiatry and director of the Child Trauma Research program at UCSF, “it is not possible to practice environmental health without knowing what Freiburg wrote about the inner life of the parent and adding the inner life of children and early defenses in infancy.” Known as Infant-Parent Psychotherapy or (IPP), this approach to infant mental health included home visits with patients, guidance and education, support, and highly individualized psychotherapy. Fraiberg’s contribution to infant mental health was based on her 15 years of research on the development of children who experienced blindness and her book, Insights From the Blind: Comparative Studies of Blind and Sighted Infants. Instead of interpreting the actions of these infants as desperate; she reclaimed their agency and emphasized the resiliency of their egos.

Advocated for addressing intergenerational childhood trauma – She argued that if a parent experienced harm and/or abuse as a child and has not been adequately treated for this past then the infant will endure a similar childhood. Ghosts perpetrating harm will come in the form of traditions and will appear during specific times (feeding, sleep, or toilet training, for example), damaging the bond between parent and infant. Participating in psychoanalysis, development psychology and social work as individuals and as a family can stop history from repeating itself.

Carol Hardgrove

Carol Hardgrove (Aldrich Gilbert) (1921-2016) was born in St. Louis, Missouri. She moved to Pasadena, California as a teenager where she attended Pasadena Junior College, and then continued her education at Whittier College’s Broadoaks School, a nationally recognized center for the professional development of early childhood educators. In 1946, after a short time in Portland, Oregon, she moved to San Mateo, California and became the Director of the San Mateo Parents Nursery School at the College of San Mateo. Hardgrove earned her BA (1962) in Early Childhood Education and her MA (1964) in Counseling and Guidance from San Francisco State College (now University, SFSU).

Hardgrove was an early childhood educator, practitioner, and influential researcher. She taught courses at various institutions, including UCSF, SFSU, and City College of San Francisco (CCSF). In 1965, she joined the UCSF Department of Family Health Care Nursing as Assistant Clinical Professor and then Associate Clinical Professor. She was the liaison between the School of Nursing and the Marilyn Reed Lucia Child Care Study Center, a center she helped found in 1978. Hardgrove also directed the Intergenerational Child Caregiving Project, a program to prepare older adults to work with infants and young children.

Carol Hardgrove’s influence stretched beyond the Bay Area. She was a Fellow of the International Congress of Pediatrics and Educational Consultant to Project Head Start. YEARS. In 1971, she embarked on a global project funded by a World Health Organization Fellowship funded to investigate policies of parental inclusion in pediatric hospital care and the use of play as therapy in European hospitals. Her findings contributed to a cultural shift in pediatric hospital care.

Hardgrove lived most of her adult life in the Bay Area where she raised four children and married twice after her first husband passed. She died when she was 94 years old.

What makes her a developmental-behavioral pediatrics pioneer?

Hardgrove was a trailblazer in family-centered pediatric care and a child-centered approach to early childhood development. She successfully advocated for changing US protocol which prohibited and did not accommodate for parental involvement in pediatric hospital care. She also championed a whole child approach and the importance of unstructured play in early childhood development. She believed children should be allowed to grow and develop on their own terms.

Hardgrove (Carol) Papers, digitized collection on Calisphere

The Hardgrove collection consists of newspaper clippings, journal articles, biographical materials, lecture notes, correspondences, questionnaires sent to US hospitals and responses, reports and material from European and US child care facilities and hospitals, hospital games and programming material for children and families, photos from Erik Erikson’s 1982 visit to UCSF, photos depicting family-centered care and children at play, training manuals, published and unpublished manuscripts.

Care of children in hospitals

Page 133 of 138

Southern California Affiliate, Association for the Care of Children in Hospitals, seminar program, “Care of Children in Hospitals” – “Parents and Professionals in Partnership,” January 23, 1980. This one-day seminar intended to bring parents and professionals together to encourage collaboration during their child’s hospitalization. Carol Hardgrove led the “Preparation – Who Prepares The Child?” workshop.

Creative uses of play

Page 2 of 20

Photograph, “N1 56 – Creative Uses of Play with Young Children, 3 units,” nd. This photograph accompanies the a course syllabus emphasizing the need for promoting imagination and play. For Hardgrove, friendly adults, children-only spaces and amorphous toys like blocks and sand promoted a creative environment ripe for play and learning.

Song sheet

Page 90 of 155

Carol Hardgrove, “Songs for Out-of-doors,” from the course “Play as a means of expression and growth,” UC Davis extension, nd. She was a fierce champion of the joy and potential of songs, as they allow for a child-centered approach to early childhood development.

Key contributions

Championed Parent-Inclusive Units and family-centered pediatric care in hospitals – Findings from her research of US and European hospitals showed that children were better adjusted and less traumatized by hospitalization when parents were actively included in their care. While almost unheard of in the 1960s (10% in 1963), parental involvement became mainstream by the late 1970s, with 80% of US children’s hospitals and 50% of general hospitals reporting having accommodations to promote parent participation in pediatric care.

Advocated for the centrality of unstructured play in early childhood development – Hardgrove taught and wrote about the value of learning through playing as it allowed for the discovering of muscles, capacity, and self-awareness. She taught courses in the School of Nursing at UCSF on the importance of play including, Creative Uses of Play with Young Children. She also helped with the creation of a demonstration play unit at SFGH.

Helped usher in a child-centered approach to early childhood development – Hardgrove believed “[s]elf-understanding and self-acceptance leads to self-actualization, responsibility and creativity; all traits sorely needed if we are to remain a democracy and a free country.” If adults satisfy basic needs (nourishment, sleep, safety, etc) and understanding then children can grow on their own terms instead of adhering to an artificial timeline. As Hardgrove put it, “you don’t make frogs earlier by cutting off tadpoles’ tails.”

Teaching questions

- How did these pioneers center the child in their work?

- How did they address the mind-body connection?

- Create a timeline of their collective contributions to Behavioral and Developmental Pediatrics.